The future of farming

As the Agriculture Bill goes through Parliament, what issues do young farmers face?

Although the number of students in Agriculture degrees is rising in the UK, there are not many farmers who can live the dream of owning their farm, without benefiting from subsidies, a family farm, or an easy job. Societal changes such as veganism, a fonder interest for animal welfare and constantly changing policies are not helping either.

This year is even more particular as it sees the passage of another Agriculture Bill through Parliament. In June, the first bill to be voted virtually is finally reaching its second reading in the House of Lords, after its initial proposal in 2018. The many disputes around Brexit and the following coronavirus crisis put a halt to what the National Farmers' Union President Minette Batters called “one of the most significant pieces of legislation for farmers in England for over 70 years.” Indeed, the text is meant to replace the CAP (Common Agricultural Policy), the partnership that unites and divides so many farmers around Europe.

Many asked: “What has Europe ever done for us?”

In terms of agriculture, the CAP has had a big impact on Britain, by providing income support for farmers through direct payments and rural development, which Defra (Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs) estimates that it represented 55% of farm incomes in 2014.

With this new Bill, Defra’s goal is to shift away from the original system of granting subsidies according to the amount of land one owns towards a “public money for public goods” where focus is moved towards environmentally friendly productions. Among other provisions, the necessity to replace almost £4bn received from the EU for subsidies, helping new entrants in the industry and making provision about agricultural tenancies.

With the UK leaving the EU, another worry builds over the head of farmers: the trade deals which could see lower quality food imports compete with British standards. The farming industry also witnesses another big problem: the decline in the number of farms, and persistently low workforce numbers.

Out of the 470,000 farmers in the country, only 3% are young farmers, which comes as a failure from industry leaders and politicians to encourage youngsters to regenerate the workforce.

Behind the reasons as to why young people do not go into farming, the investment required ahead and the lack of a family farm are among the main issues.

President Donald J. Trump participates in a bilateral meeting with British Prime Minister Boris Johnson Tuesday, September 24, 2019, at the United Nations Headquarters in New York City. (Official White House Photo by Shealah Craiughead) ©Flickr/TheWhiteHouse

President Donald J. Trump participates in a bilateral meeting with British Prime Minister Boris Johnson Tuesday, September 24, 2019, at the United Nations Headquarters in New York City. (Official White House Photo by Shealah Craiughead) ©Flickr/TheWhiteHouse

A survey carried by NatWest and the Royal Bank of Scotland on 517 young farmers whose results were published in 2017 shows the barriers of entry to farming. © NatWest/RBS Agricultural-Report

A survey carried by NatWest and the Royal Bank of Scotland on 517 young farmers whose results were published in 2017 shows the barriers of entry to farming. © NatWest/RBS Agricultural-Report

Gregory Harrison produces organic fruits and vegetables in Suffolk. ©Gregory Harrison

Gregory Harrison produces organic fruits and vegetables in Suffolk. ©Gregory Harrison

Seed starting trays with lettuce seeds. ©Gregory Harrison

Seed starting trays with lettuce seeds. ©Gregory Harrison

Young sprouts in trays. ©Gregory Harrison

Young sprouts in trays. ©Gregory Harrison

Vegetable box with mixed products, leeks, salads, winter vegetables. ©Gregory Harrison

Vegetable box with mixed products, leeks, salads, winter vegetables. ©Gregory Harrison

A Hard Row to Hoe

For Gregory Harrison too, farming has not been a family affair. In 2017, the 34-year-old set up his enterprise Sunshine and Green in Wickhambrook, Suffolk and produced organic fruits and vegetables until December last year, when he had to stop his business.

“For me personally, the problem at the moment is access to land,” he says.

“It's a disaster. I mean, it's a nightmare.”

For the past two years, Gregory was a tenant on a farm but has been looking for a place where he can grow his business to add value for himself instead of adding it to someone else’s. With extra costs such as investments in the venture and expensive infrastructure, the project of owning his own parcel became a shattered dream.

“Land prices in this country, in Suffolk where I am, are anywhere from £10,000 to £15,000 an acre. Actually, what I'm seeing is people are paying closer to £20,000. Because if you have small bits of land, people want to put horses on them. And for the other farms around here, a small field is 50 acres, and farmers don't really want to let them go,” says Gregory.

Evolution of the number of farms and areas by agricultural size of farm in the UK between 2005 and 2013. (Source: Eurostat)

The difficulty to find land is not new though.

In 2014, The Guardian already reported that prices were rising and that county farms crawled under applications for tenancies. Owned by local authorities, these farms are meant to help new people into farming by lending them a smaller area than what the majority of farm businesses require. For Gregory whose goal is to start with a reduced farming area to grow his organic products, the land available comes into a portion way bigger for what he needs.

“I put an application in for one. The difficult part of it is that I want to grow vegetables, and basically in this area, there's no one else growing it. It's more or less all arable.

Gregory explains the mindset behing growing organic fruits and vegetables.

Gregory explains the mindset behing growing organic fruits and vegetables.

"So the farm I found that is available, a council farm, is 117 to 120 acres, which is too big for me starting out growing veg.

"Fruit and vegetables are very labor intensive.

"So for me to take on 120 odd acres straight off the bat is far too much. I have put in a special application for it, to try and take on 25 acres which is still a bit too big, but I would do it.

"And as yet, they said they would be back with their answer at the start of April, and we haven't heard anything back from them since, which is a bit annoying.”

Killing two birds with one stone

One of the big problems young farmers have today is the ability to set up a business. Even with a foot in the farm through his family, this is what William Roobottom experienced in Staffordshire.

At 23, the young farmer has just handed his dissertation on trace elements for his degree in Agriculture and business management at Harper Adams University.

“When I was at college, it just opened up my eyes to all the different forms of farming,” says William.

“At home we are just a grass-run farm and we produce hay and haylage for the equine world. Once in college I learnt all about livestock and arable. Then I brought some sheep onto the farm.”

Although his father and grandfather who own the 500-acres Hamstall Ridware family farm weren’t so keen at first, William saw the potential of investing in sheep whose flock could grow on the unused hill behind the family house.

“I kept asking if we could get sheep and in the end, I just went and bought five ewes, which expanded quite rapidly and we went from about 30 to 150 in two years,” he says.

With 200 lambs and 130 ewes today, the goal for William is to grow the flock without affecting the farming production, and use the mowed hay land for his sheep to graze.

“Down the line, my grandad and my dad have both been very supporting and they see it definitely helps the enterprise because it is utilising a waste product which is not being used, so it's adding to the current business.”

“As it’s part of the family farm, financially it’s not as much of a struggle, but I do understand that for other people, like some of my friends who are young farmers and starters, it’s hard because it's quite a large overhead to start and banks aren't so keen to loan to people without any background,” concedes William.

He also recognises that the industry can seem volatile and unpredictable, with very good times and very bad times. One of his wishes is that people buy more British products.

“Eating British should be a cheaper alternative to imports. It’s hard because there is so little out there about British agriculture and the general person doesn’t actually know a lot about it.

“That is why I have just started a new Youtube channel on science for people to learn about little things about sheep farms and just to increase what people know about British farming.

“If everyone does a little bit, it helps just to broaden people’s knowledge out there.”

William has just started his own Youtube channel "On the farm with Will" where he gives tips with sheep flocks.

William has just started his own Youtube channel "On the farm with Will" where he gives tips and how-to with sheep flocks.

“Farming is completely different to a lot of other industries.

"It’s being able to go out of your front door and knowing that most of your time at work is outside in the countryside, and it puts a smile on your face.”

William Roobottom

Anna Hunt with a heifer calf. ©Anna Hunt

Anna Hunt with a heifer calf. ©Anna Hunt

Three veals ©Anna Hunt

Three veals ©Anna Hunt

Anna is also a NFU Student and Young Farmer Ambassador. ©Anna Hunt

Anna is also a NFU Student and Young Farmer Ambassador. ©Anna Hunt

Pig in a Poke

Although ministers have assured that lower quality food imports will not be considered in trade deals that the country will seek after its departure from the EU, many worry that the absence of procedures on imported food will lower standards and will bring an uneven competition with British farmers.

Our #AgricultureBill will unleash the potential of farmers and land managers in England to produce more food while improving the environment for generations to come.

— Defra UK (@DefraGovUK) January 16, 2020

Check our Facebook later today for more details.

Read our press story now: https://t.co/AFiORihiUw#futurefarming pic.twitter.com/XXcxOxTFIR

“I think people don't realise how important it is that we protect the standards in each country,” explains Anna, a 20-year-old farmer and biology student at Durham University.

“If we're allowed to import products that are below standard than ours, then potentially if they are the same price or cheaper, obviously it's going to outcompete our farmers.”

Like 987,887 others, she signed the NFU petition demanding that imported food be subject to the same regulations as UK farmers have to abide by. The petition came up after an amendment to the Bill was presented in Westminster by chairman of the Environment, Food and Rural Affairs Select Committee Neil Parish and would have banned low standard food imports from entering the UK. Although the amendment was supported across parties, it was defeated by 51 votes in Parliament.

“We could be about to open the floodgates to a whole raft of low-quality food that would normally be illegal in the UK” - @jamieoliver urges @BorisJohnson not to betray British farmers and our high food standards in future trade deals 👏🏻🇬🇧 https://t.co/tTK086Vlfi

— National Farmers' Union (@NFUtweets) May 31, 2020

As a NFU Student and Young Farmer Ambassador, Anna is brushed up on politics in agriculture and regrets that numbers of young people interested in the future of their industry aren’t higher.

“I think that farmers care, and the public would also care if they knew what it meant for their food,” she adds.

She also recognises that the perception of the industry might be a bit backward, with a lot of manual labour and that it is a deterrent for many young people.

“I believe it is one of the industries with the most states for growth and innovation in technology,” she says.

“Things have become more automated, we have tractors now that will basically drive where you can lift the implement out at the end of the run. It can turn and go back in without you touching anything.

“I think farms of the future won't be made of strong people but they'll be computer scientists.

"It's an exciting industry to be part of."

Far from Durham, on the Isle of Wight, Jack Hodgson is wrapping grass in bales for animals to be fed next winter. The 27-year-old comes from a farming family too, and after sport studies and a few years teaching climbing in the Dolomites in Italy, he came back to his original background and studied Agriculture Management at the Royal Agricultural Society.

“That sort of opened my eyes to the potential that can be made in farming,” he says.

Since he left university at 22 year old, he has been working on the family-owned Cheverton Farm, producing sheep and beef meat for restaurants and shops, as well as cultivating arables on a 730-acre plot. Although not regretting his decision about a career in agriculture, Jack concedes the difficulties in farming today.

“I would say the majority of farming has to be on a big enough scale to justify the manpower and the costs,” he adds.

“Small farming is difficult nowadays, it’s very, very difficult to make it work well.

“I think that is why farms like that have diversified massively into tourism or into a small farm shop. You've got the potential to make more money at work because you've got less risk overheads.”

Like many other farms in the UK, Cheverton Farm receives subsidies from the European Union through the CAP.

“It subsidises the cost of production, the fuel costs, the transport, the drugs.

“Everything in this country is at a higher rate because we are under higher welfare standards and that is pushed on us from the European Union.

“And for a good reason, you can't produce a product without high welfare, however it comes at a cost.”

Estimated at £4 billion each year, subsidies from the CAP scheme will be phased out, in a move which has been criticised by the Scrutiny committee, who revealed in 2018 that no further information had originally been provided by the Government about what might happen to direct payments after 2022.

Since then, a timeline was drafted, describing the way the government plans to phase out the payments, while reducing their amount. Farms in the higher payment band (£150,000 or more) will see their subsidies reduced by 25%, while smaller farms, who receive up to £30,000 will lose up to 5%.

“My opinion on the changes that are happening is that if we can survive through them financially and mentally then I think the future is brighter for UK agriculture,” says Jack.

With a positive outlook, Jack explains that the pandemic this spring has really been the issue on its mind lately. Farmers around the UK have had to face production issues, faced with a lack of seasonal workers to pick up fruits and vegetables.

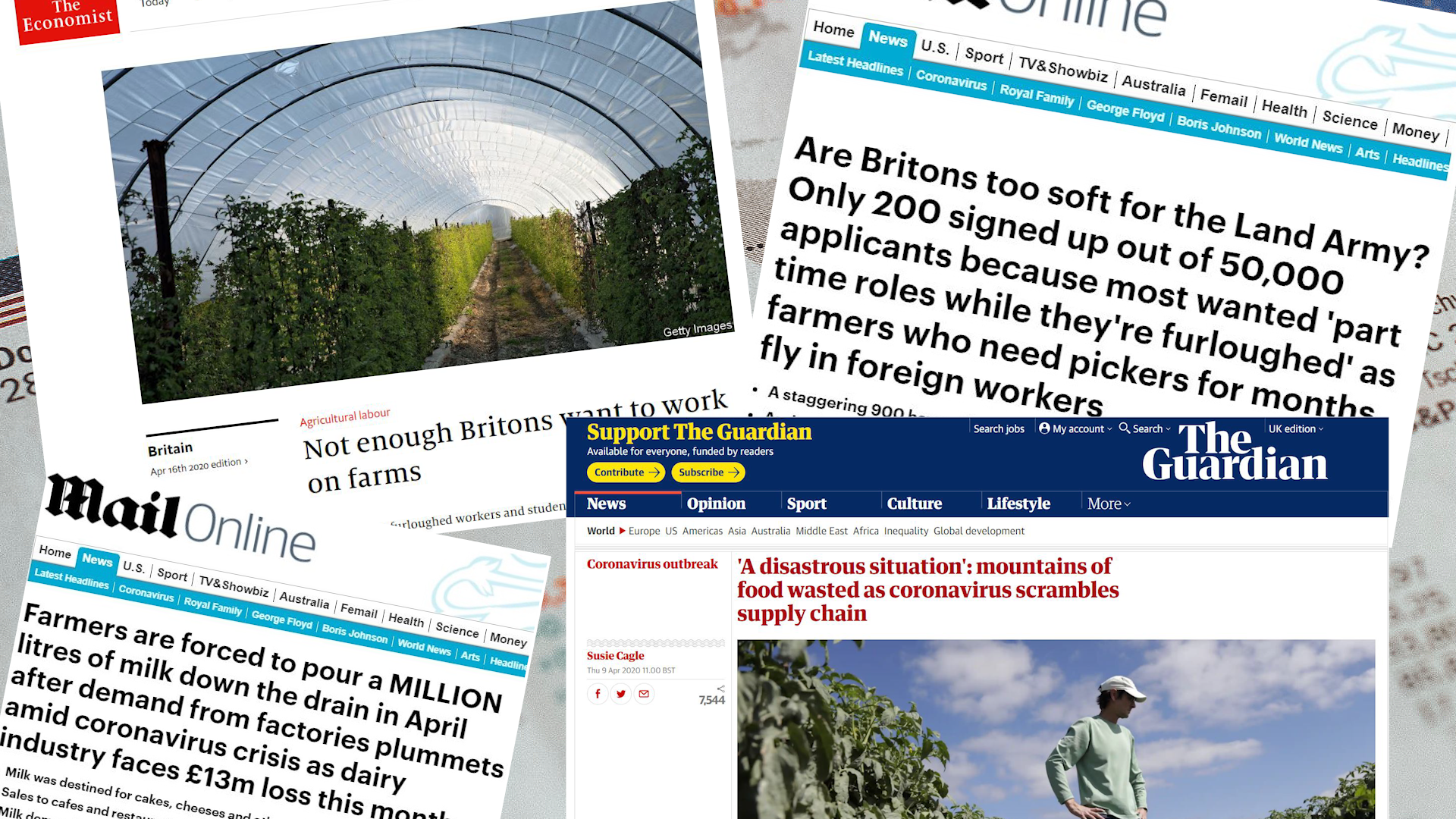

The COVID-19 pandemic has hit farmers all around the UK, and made the headline of newspapers during spring.

The COVID-19 pandemic has hit farmers all around the UK, and made the headline of newspapers during spring.

At Cheverton Farm, beef meat usually sold to restaurants has been piling up.

“Beef prices are horrendous on the general market,” he adds.

“We have prime steaks stacked up not being able to sell because there's no restaurants open at the moment.”

“COVID-19 is hard, you are working flat out because it's that time of year but you can't do anything else. So mentally, I think for us, it's slightly harder.

“It’s stressful but farming is a very long game.

“You have to set your sights a long way in the future. I mean, potentially you're putting a crop in the ground, and you can't predict how much you're going to get for that, that’s a huge risk, but that’s farming.”

Until the Cows Come Home

In the south west of England and Wales, another epidemic has spread, creating thousands of pounds of economic disruption and adding to the worry of already distressed young farmers. Since the 1980s, bovine tuberculosis (TB) cases have been multiplying in various regions of the south west, infecting cattle as well as deers, badgers, and other animals living in the wild. In 2019, although the numbers of infected-cattle slaughtered in England has seen a decrease of 6% from the previous year, 31,102 diseased cows were sent to the slaughterhouse.

For Sarah Eva, 34, and her husband David, 36, who manage a beef and dairy farm in Helston, Cornwall with 220 cows in total, TB almost saw the end of their business three years ago.

“In 2017, we nearly had to stop farming because we lost 91 cows due to TB,” says Sarah Eva.

“It has finished so many farms, because even though you get compensation, the money you get is based on the age of the animal," she adds.

"You might have two cows next to each other, they might be the same age but one might be a really good milker and a nice shape, and the other one might be really thin and not give much milk but you get the same money for it.”

Her husband David, an eighth-generation farmer, has followed through the steps of his father in the close farm, meaning no other animals are bought to supplement the flock.

“Sometimes if you get TB, it’s because you bought an animal that has got TB and you’ve brought it into the farm," Sarah continues.

“So because we were close, they had to come from the wildlife. It’s a bit frustrating because the badgers are carrying the TB as they do all over the country."

David, Sarah and their four children. ©Sarah Eva

David, Sarah and their four children. ©Sarah Eva

Sarah, who has four children from 7-weeks-old to 6-year-old and teaches two days a week at Devoran Primary School, is not the only one concerned about the impact of the disease on her farm.

"It was a worry because we all have to be tested for TB," she says.

"We all had to have blood tests and David's parents had their chests X-rayed and our children all had to have blood tests.

"We're all okay and I think that's the most important thing."

The badger cull has been a controversial topic in the UK, with associations protecting animals voicing their concerns against the killing of this species. Research conducted at the Zoological Society of London in 2013 even shows that bovine TB is not passed on by direct contact between badgers and cattle.

Yet, the number of contaminations has spread in the past few years, leading to tragedies such as seen in a recent report of Farmers Guardian, where four farmers committed suicide following the Government’s decision to stop badger cull in Derbyshire.

In Pembrokeshire, Rebecca John, 19, works on Rinaston Farm with her father and her grand-father. She is also a second-year student at Aberystwyth University, learning about agriculture and business. When she is not milking cows and feeding calves, she is thinking about her plans to go abroad once she graduates.

“So I've got another year left, and we hopefully will go back to normal,” she says.

“And I want to go travelling after, to New Zealand and America and Canada, just to broaden my experience a bit more. And then hopefully return back to the family farm then.”

For the young woman, the future is all planned, just like the subject of her dissertation in third year: it will be bovine TB.

“I think this is the biggest problem we have on the farm.

“We’re testing every sixty days, which is a lot of manual stress, physical stress and mental stress, and for the cattle as well.

“The cattle are being tested, and they either come back as reactors, or as IR which is inconclusive results.

“A few times we've sent cattle off for slaughter because apparently they had TB but the results have come back clear.”

Rebecca explains that according to her, the tests are not reliable enough, and that more studies should be done into the difference between skin tests and blood tests.

“I'm not allowed to do my third-year project on that because I can't go into the lab so I'm doing a project based on how it's affecting the mental health of farmers,” she says.

And a lot of work needs to be done on that topic too. Recent articles published in 2020 show that mental health has a direct impact on farm safety, for a profession that bears long hours in isolation.

When she's not on the farm, Rebecca John studies at Aberystwyth University ©Rebecca John

When she's not on the farm, Rebecca John studies at Aberystwyth University ©Rebecca John

©Rebecca John

©Rebecca John

Rebecca and a cow ©Rebecca John

Rebecca and a cow ©Rebecca John

Cow ©Rebecca John

Cow ©Rebecca John

Nonetheless, Rebecca, like many other young farmers, remains positive about the future of her industry. She welcomes the green improvements that the Bill will bring into effect. And as many issues the sector encounters, there are always positive notes to find.

In Wickhambrook, as we finish our chat, Greg receives a call. Suffolk County Council has accepted his application and scheduled an interview for him to present his project for an organic farm.