Moving in the right dye-rection

How Greater Manchester is embracing plant dyeing as an alternative to fast fashion

Before the industrial revolution, naturally-derived dyes from roots, berries, and wood were used as the main method of colouring clothing.

The process took several weeks and was a luxury only the richest in society could afford.

But how did this once slow-moving process turn into the hustle and bustle of today's fast-fashion industry?

In the mid-nineteenth century, the first synthetic dye was introduced.

Production became cheaper, less dye was required, and a high volume of clothes could be manufactured very quickly – pre-empting the rise of so-called ‘fast fashion’.

Audrey Bate is the owner of a small business called 'CosyOrganic'. She uses all-natural materials to make her clothes, including dyes.

Audrey said: "If I'm using a natural dye, I know step-by-step every ingredient that goes into the process.

"But if I'm using a chemical I've got no idea about what's in it. Fast fashion tells a completely different story: the ethical responsibility isn't there."

Manchester, as home to the headquarters of global fashion brands such as Boohoo, Missguided and JD Williams, seems to have become the UK's central location for fast fashion.

However, small artisanal businesses in and around Greater Manchester have begun to challenge the huge toll that the synthetic dyes used by these fashion giants are having on the planet.

History of Manchester as a clothing capital

Manchester’s history as a city is rooted in textiles and fashion. In fact, its very foundation was built on its association with the cotton trade.

Manchester was built on the success of its cotton mills which, alongside its warehouses and busy streets, made it the world's first industrial city.

HOME OF TEXTILES: The Science and Industry Museum in Castlefield, Manchester has displays exploring the city's history as the UK's industrial base for cotton and textiles.

By 1853, the number of cotton mills in Manchester reached 108. This was the peak of the cotton trade in the city.

The very next year, Manchester gained the title of ‘Cottonopolis’ – as it became famed for being the centre of the cotton industry.

COTTONOPOLIS: Manchester's cotton mills revolutionised the fashion industry.

Shortly after this, in 1856, the first synthetic dye was discovered by Sir William Henry Perkin.

The purple-coloured dye, known as Mauveine, is made from coal tar. Its low production cost meant that fashionable items, previously only worn by the upper classes, could now be worn by everyone.

Perkin's notebooks are held at the Science and Industry Museum in Castlefield, Manchester. If you look closely at the pages in a picture on their website, you can see purple fingerprints made by the dye:

Mauveine was an alternative to Tyrian purple: a luxurious and expensive natural dye that came from sea snails and was widely used up until the industrial revolution.

Synthetic dyes are vital to the operation of the fast fashion industry. They make for cheap and easy application to clothing, high volume manufacturing, and brighter colours.

Fast fashion relies on inexpensive clothing produced rapidly in line with the latest trends. The quality is compromised, meaning that customers buy more clothing and throw more away. The industry is associated with the exploitation of cheap labour, often in sweatshops and poor working conditions.

According to the UN, the average consumer buys 60% more pieces of clothing – with half the lifespan – than they did 15 years ago.

And so, in the twenty-first century, Manchester’s prominence in the textile industry remains.

Home to numerous online fast-fashion brands, shopping centres and clothing outlets, Manchester is well on its way to becoming the fast fashion capital of the UK.

The map below shows the density of just some of the fast fashion outlets and headquarters in Manchester city centre.

MAP: Fast fashion in Manchester. Manchester is home to headquarters of big brands such as Missguided, Boohoo and JD Williams, while also offering a range of fast fashion outlets to the public.

Which are more eco-friendly: natural or synthetic dyes?

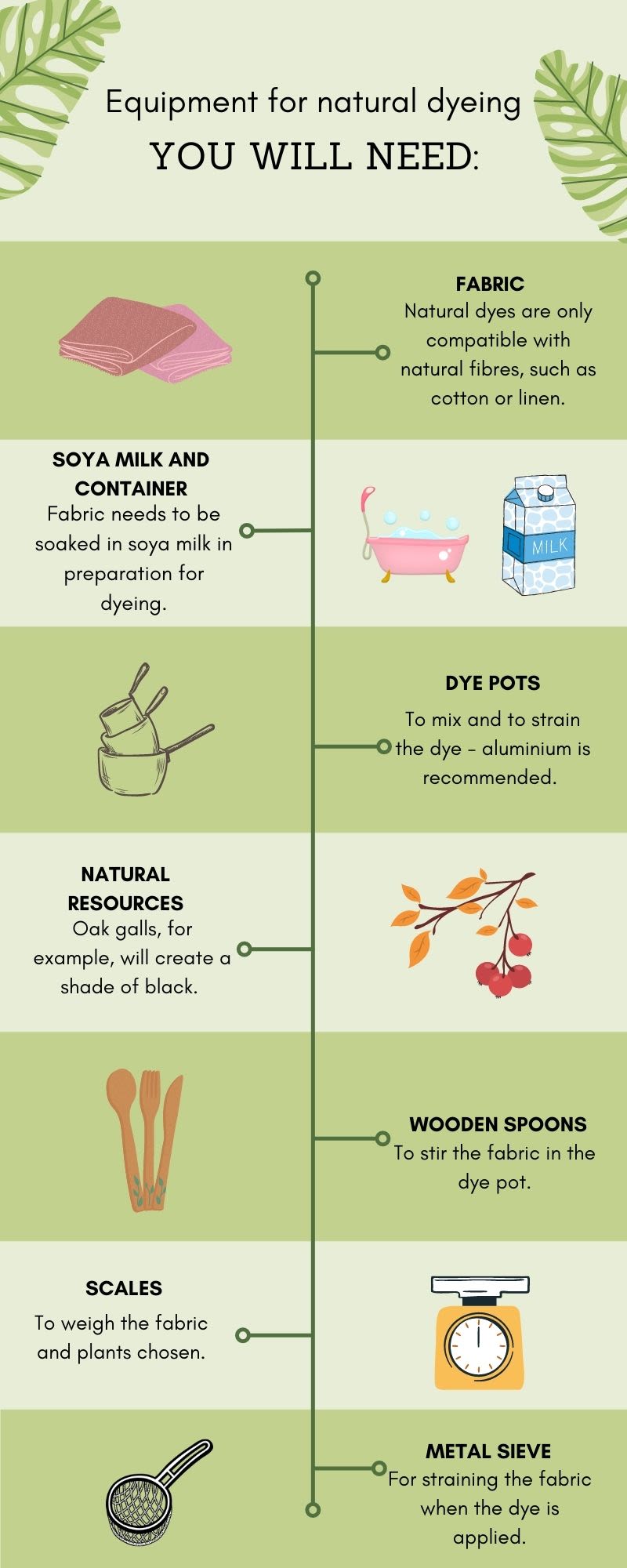

Natural dyeing practices have experienced a resurgence in popularity over the past few years. Unlike synthetic dyes, natural dyes are biodegradable, non-toxic and non-allergenic – meaning they are better for the wearer’s skin and, for the most part, are better for the environment.

However, they are less permanent, seasonal, and more difficult to apply. A large amount of water is still required for the dyeing process to take place and the dyes only adhere properly to natural fibres.

Synthetic dyes also require a high water usage in their production and during the process of being applied to the cloth.

In addition, a large factor in the detrimental impact of fast fashion as a whole is the passing of synthetic dyes from factories into nearby rivers.

In some cases, chemicals have dyed whole rivers and killed nearby wildlife. For example, in 2006, the Mao Zhou river in China turned red as a result of contaminated dye water released from a large mill.

According to the Biotechnology Research and Innovation journal, 80% of the total emissions produced by the textile industry result from the discharge of untreated effluents into water. A large percentage of this is caused by synthetic dyes.

It is no wonder that small businesses are trying to lead by example in introducing plant dyeing methods into their manufacturing processes.

COMPARISON: The pros and cons of natural and synthetic dyes.

COMPARISON: The pros and cons of natural and synthetic dyes.

Greater Manchester may now be synonymous with the fast fashion industry, but small businesses in the surrounding areas are working hard to combat this reputation.

One such example is Audrey Bate, who launched her organic clothing company 'CosyOrganic' in September 2021.

Based in Appleton, Warrington and originally from Dublin, Audrey began to experiment with plant dyes after her three-year-old daughter Harriet developed severe eczema as a result of wearing clothing made with synthetic dye.

“I wanted to create a company which had a positive impact on the environment. Natural dyeing is a slow and gentle process with amazing natural results.”

The designer currently specialises in a range of bedding and children’s clothing, including dresses, pillows, and hats.

RANGE: CosyOrganic features bedding and children's clothing, all using natural materials and dyes.

She also intends to combat the environmental damage caused by fast fashion brands by using recycled paper and offcuts from her studio for packaging.

Audrey mainly dyes her clothes using tea, safflower and oak galls, which she gathers from around the local area.

The natural dye expert acknowledges that the nature of the plant-dyeing process means the colour of the fabric is not always evenly spread.

She said: “These beautiful ribbons have tiny little shades on them but there’s a story that comes with that. It’s not manufactured a million times over.

“Instead, it’s done on a really small quantity of cotton and you buy into the labour that’s gone into it. It adds beauty to it.”

INDIVIDUALITY: No two plant-dyed items are the same – as seen here in CosyOrganic's ribbons.

Audrey is open and honest when admitting that the hard work that goes into the plant dyeing process means that the price of her products is higher than on the high street.

Factors such as the intense labour required to dye the ribbons, as well as working in small batches and using ethically-sourced materials, all drive up the cost – but the reward is a unique item.

She does, however, realise that not everyone is able to afford ethically-dyed clothing.

Audrey said: “The process and effort of slow fashion come with a cost not everyone can afford.

“I think it’s important to respect that we are not all in the same position to make these decisions.”

THE COST OF SUSTAINABILITY: Comparing CosyOrganic's prices to its Primark equivalent shows a vast gulf between the two and the price that comes with slow fashion. Data sourced from CosyOrganic and Primark websites.

Audrey’s main goal for her business is to work with other small companies like her own to make larger brands pay attention.

The combined efforts of small artisanal plant dyers seem to be taking effect.

Larger brands such as Levi's and Converse, as well as Mango and H&M, have started introducing plant-based dyes, meaning that more nuanced colours could start to become a regular occurrence on the high street.

How to: Plant Dyeing Tutorial

“You just learn by experimenting”

Plant dyeing may sound like a complex process, but Audrey says that, with some reading and practice, anyone can dye their own clothes at home. The equipment needed is fairly basic and a lot of it can be found around the house.

Audrey mainly uses oak galls, safflower and tea to dye her clothing – but says that you can find many more options just by exploring the plants in your local area.

These dyes all have a high colour payoff and are relatively simple to apply, although safflower requires the pH of the water to be changed. The dyeing process can be long at up to six weeks per item but the results reflect the time and energy that has been put in.

Audrey shares her best tips for getting started with dyeing using oak galls in the video below:

HOW TO: Audrey Bate, owner of CosyOrganic, shares her method of plant dyeing.

With some research and exploration of dyes and plants, anyone can begin to dye fabrics from home.

Two rival markets are emerging in Greater Manchester: there is the continued and unprecedented growth of the fast fashion industry which shows no sign of slowing down. At the same time, the work of small artisanal plant dyers, of which CosyOrganic is just one of many, is quickly catching on.

As larger brands start to pay more attention to their ecological footprint, plant dyes could once again start to become a staple method of pigmenting textiles.