Money for nothing?

There is a radical welfare solution on the horizon that gives everyone (yes, everyone) a lump sum each month - and campaigners are proposing Manchester as the second place in the UK to host a trial.

What would you do if you were given £1,600 a month with no strings attached?

Buy better food? Put it in your savings? Start a new hobby, or change careers?

For more than 600 care leavers in Wales, that question was not hypothetical.

Between 2022 and 2024 the Welsh government ran the first basic income trial in the UK, giving £1,600 pre tax to 644 young people who had turned 18, aging them of the foster care system.

While we wait for their findings, a campaign proposing that Greater Manchester be the second place to trial a similar scheme is gaining ground.

In collaboration with researchers at Northumbria University, the Basic Income Research Group and the Common Sense Policy Group, campaign group UBILab Manchester released a proposal policy paper in February 2025.

The proposed pilot gives £1,600 a month to those they see as the region’s most vulnerable group: young people from disadvantaged backgrounds who are either at risk of or currently experiencing homelessness.

And the idea has already seen endorsement from Greater Manchester Mayor Andy Burnham.

He said: “A universal basic income will put a solid foundation beneath everybody so that they can have a life with security and stop worrying about everything.”

In his 2024 manifesto, he said that the housing first trial showed that by setting people up to succeed, most will - saving money in the long run.

He wants to see a basic income pilot as the next step.

Dr Elliott Johnson, a fellow in Public Policy at Northumbria University and one of the co-authors of the proposal for Manchester, explained: “Young people have borne the brunt of ongoing austerity measures since the Global Financial Crisis.

“Andy Burnham has rightly prioritised preventing homelessness in Greater Manchester - this pilot is an opportunity to deal with that crisis at root – by giving young people the financial security that they need to make longer-term decisions that secure their future.”

Opponents of a basic income fear it will encourage unemployment and cost more than the existing social security system.

Despite support from the mayor and interest from across the political spectrum the plan hasn’t gone further than a proposal as it waits for the necessary funding. Any pilot that does happen would probably be run privately, not through the council or other public body.

Funding could come from a private grant, research funding, public donation, public funding through central government or local authority - but most likely a combination of all of the above.

UBILabs and the academics they work with define basic income using five core characteristics:

Cash

You get it as money that you can spend on whatever you want, not as food stamps, coupons or other ring fenced funds.

Regular

You know when the next payment is coming and can plan around that income.

Individual

It's paid to an individual, not to a household or family unit. Some campaigners use this to highlight the ways that basic income can benefit those seeking to leave abusive environments.

Unconditional

Unlike the current benefits system you don’t have to work, or make any promises to get the payment. It isn’t means tested.

Some proposals also include under-18s, whether through paying into a savings account, or a having a smaller amount allocated to them.

Universal

Everyone gets it. Genuinely everyone. This point has drawn some criticism that those who already have enough money should not be given these funds by the government, but proponents of the idea point to the potential for grassroots redistribution networks, increased charitable giving and people having the freedom to quit jobs they are unhappy in.

Currently, someone needing benefits may have to apply for multiple different pots of money, like universal credit, jobseekers allowance or PIP if they’re disabled.

Many of them have to attend regular appointments that some describe as humiliating, demotivating and stressful.

A universal basic income would replace this system.

Everyone would be given a flat rate, removing the costly bureaucracy of most means testing.

"It sounds like a utopia, I can't comprehend it"

UBILab Manchester, and other advocates, suggest the idea of Basic Income+, a means tested benefit that would add to the total certain people received to support those with additional needs, who may need more than the baseline.

For some young people, it feels too good to be true.

“It sounds like a utopia. I can't comprehend it," said Freya, a 25-year-old from Manchester.

But for many looking at diminishing job prospects, rising house prices and increasing cost of living, it could be necessary to secure their future.

Cass, 19, lives with her dad and has been unemployed and looking for work for months. She lives in a rural area where there are very few opportunities and lack of public transport means she cannot travel.

If she had a basic income, she said: “I’d be able to move to someplace else.

“I would probably be able to move to someplace where there is more work available, so it would probably be easier for me to then get work as well.

“I would be a lot less stressed about life.”

Cass currently claims £300 in universal credit a month, and although the basic income proposed above would be enough to secure housing and bills for her, she says she would still get a job.

Would 21-year-old student Layla take a basic income?

“Yes. A resounding yes.”

For her, it could be a game changer.

She said: “The first immediate effect would be that the stress would be gone, because I stress over bills a lot.

“Stretching money is incredibly difficult. I would also have the ability to spend more money on food.”

"The stress would be gone"

Layla has been restricting her food for the last three years, spending only £18 a week to keep her savings going as long as she can while studying aerospace engineering at the University of Nottingham.

She said: “That's not enough to live on. And currently I'm noticing the effects because I've got an injury which isn't healing as fast as it should be.”

Layla is a wheelchair user and also leads an active lifestyle, and says that with a basic income she would be able to afford more high-protein and nutrient rich foods that would sustain her.

It is not only young people that see this as potentially groundbreaking.

Paul Collis, 42, is a chartered accountant, but on stage at an open mic event he’s Cornay, musician and songwriter.

He would take a basic income.

“I’d spend more time doing music, and try and get a career doing music. It would get me a little bit of breathing space on that.

“Working full time and having a family, it's quite limited the time I get dedicated to doing music," he said.

Paul has a stepson who he said would also benefit from a basic income because it would prompt schools to more comprehensively teach financial literacy at an earlier age.

In January 2022, the Irish Government began their first basic income trial, giving 2000 artists a weekly income of €325 (~£277). Each participant was granted a year of basic income, amounting to ~€16,900 each.

"We are all engaged in a life that could be considered a failure"

In a report published in May 2025, participants in the Irish trial reported that it positively impacted their artistic practice, and ability to be creative.

One participant said: “It made me more confident to take risks, because I wasn’t… I didn’t feel that muted shadow that you might be judged.

“Like failure is a big part of creativity, and if we’re allowing ourselves the space to fail, then more interesting work comes from it. Failure is the building blocks to art.

“In the end that’s the universal truth – we all are engaged with a life that could be considered a failure.”

UBILab Manchester has a small but dedicated team of volunteers, and works as part of an international network of UBILabs, advocating for pilots to be run in a variety of areas and contexts.

They've run meetings and hosted discussions and panels, talking to local residents and building support for the proposal.

Campaigner Louis Strappazzon, who helped to produce the proposal put before the council, said: “It's a long term investment in people.

“It provides trust in people, people start trusting the system more. There is an efficiency where you could save a lot in areas like social care and it improves and reduces mental health issues and hospital visits.”

But he stresses that while basic income could be revolutionary, it isn’t a silver bullet: “It can be a pillar of an alternative economic system.

“It won't solve everything on its own: if you want ubi to bring communities together you should also think about community initiatives and if you want to help reduce homelessness you need good social housing.”

What he says echoes an often quoted saying from the California based co-director of the Universal Income Project, Sandhya Anantharaman: “Basic Income doesn’t solve every problem. But it makes every problem easier to solve."

Critics of the policy argue that it is too costly, and not targeted enough to be a truly efficient use of funds.

And it is costly.

The proposed Manchester trial would amount to £7,680,000 for 200 recipients across a two year trial. The Welsh study has cost nearly £40 million in payments to the participants alone.

There are a variety of proposals on how to fund basic income.

UBILab Manchester believes that through poverty reduction, pressures on the healthcare system will lessen, with factors like childhood malnutrition and development, communicable and non-communicable diseases, drug use and stress related conditions all expected to reduce.

Through a better social safety net, they say that crime will reduce as people no longer have to turn to illegal activity to afford the basics.

They also project an increase in spending and entrepreneurship as everyone gets a little more room to breathe.

Many also propose progressive taxation reforms alongside a basic income, increasing tax rates on the super rich and closing loopholes.

But whether or not this would play out in practice remains to be seen.

Receptionist Becca Allen, 19, says that although she would take a basic income, she doesn’t believe it should be instituted as a policy.

“It just doesn’t seem that sustainable.”

She said that some people in her block of flats already use drugs and take universal credit rather than getting jobs, and feared that the introduction of a basic income would make this problem worse, rather than encouraging them to seek help.

But despite these concerns, it's clear that most people have a hard time saying no to receiving a basic income for themselves.

Poll: Do you think Manchester should trial a guaranteed #basicincome of £1,600/month?

— Roma Robinson (@roma_robinsons) June 13, 2025

Tell us why below!

Although the results from the Welsh study have yet to be published, a German study called Pilotprojekt Grundeinkommen (the basic income pilot project) finished a three year trial in November 2024 and made the first set of results public in April 2025.

Their basic income group was picked from a lottery, and given surveys around key areas every six months.

This study gave 122 people €1,200 per month, (~£1,000) and compared them to a control group of 1,580 people with the same demographic distribution - who did not receive a basic income.

In Germany in 2024 those working 40-hour weeks on minimum wage can expect to make €2,222 a month, €26,666 annually, and gross median salary for the country sitting at €4,323 a month, or €51,876 a year.

Net salary is significantly lower, around €30,000 per year.

Between the two groups, those on basic income put an additional €450 a month into their savings.

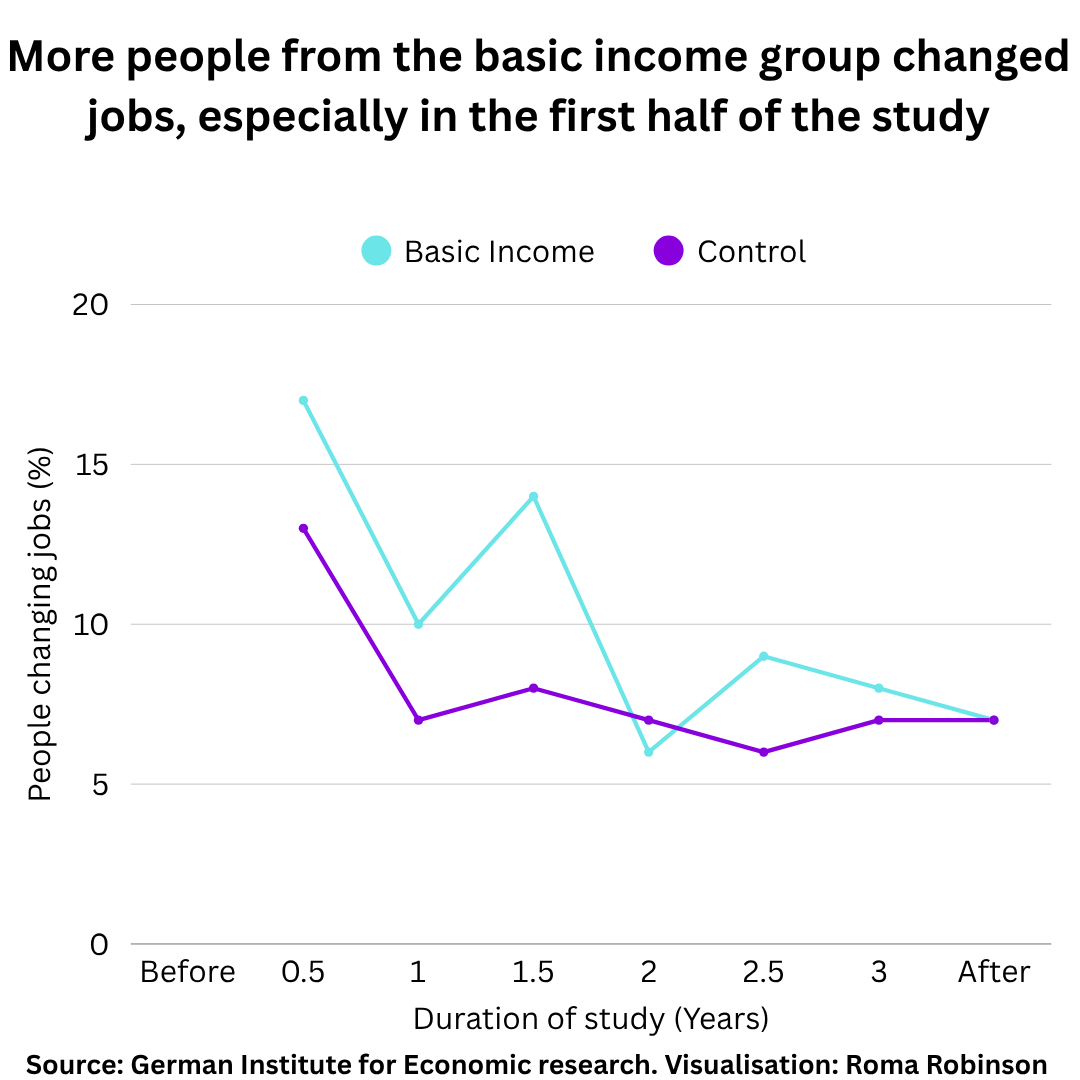

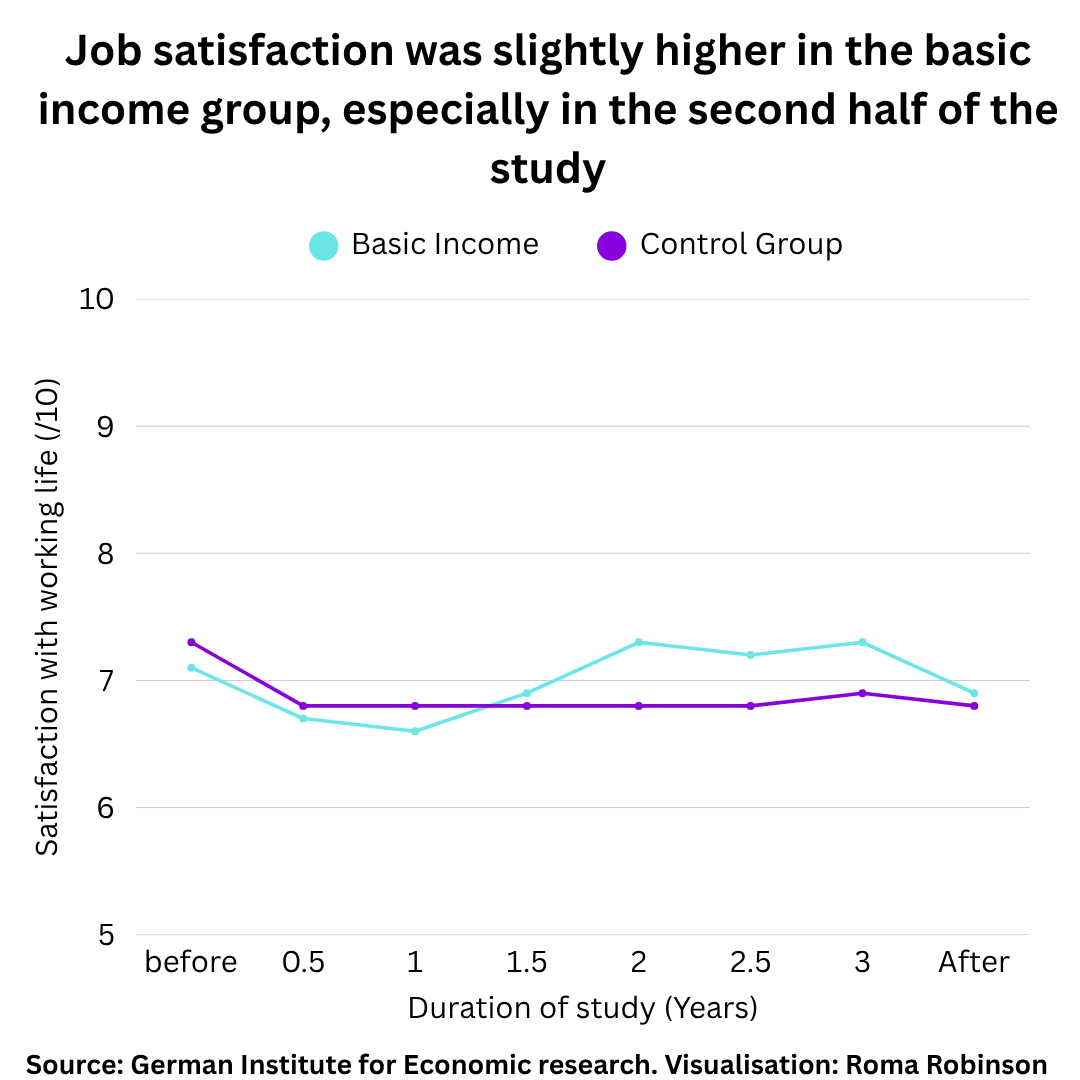

They found that employment rates were no different between the two groups. In the first 18 months of the study more from the basic income group left their job and took up others - and in the latter 18 months there was greater satisfaction in work.

Basic income participants unsurprisingly saw an improvement to their financial security, putting on average €450 (~£380) more a month into savings than the control group. They also gave more away, spending more than double a month on supporting others in their social circles and spending €20 more a month on charitable donations.

And despite the transformative potential of basic income, German researchers found it could not overcome human nature: rates of procrastination were no different between the two groups.

Unfortunately for those already excitedly rebudgetting, the proposal remains only that. UBILabs Manchester is now looking for funding, and the commencement of a trial could be a few years out.

Picture credit: Pixabay and UBILab Manchester