Les Banlieues

The story of the neglected French suburbs

Nestled around France’s major cities, the residents of the Banlieues sit and watch from the outskirts through slits of glass in their faceless high-rise flats. Meaning ‘suburbs’ in French, the Banlieues have come to symbolise the urban and societal failures of modern France struggling to come to terms with how it wants itself to look and what it wants itself to say.

These areas, once marshlands populated by outlaw bandits working outside the city walls, are now home to millions – many from North Africa and the old French colonies who settled after arriving to help rebuild France following the Second World War.

Poverty, unemployment and crime run rife in these neighbourhoods. Lack of opportunities, access to healthcare, a judiciary that only looks down and police violence are also the grim constants for residents here. Constants that have been neglected for decades.

The concrete crusts of Paris are some of the worst in France for these issues. Grigny, which sits south of the capital is the poorest suburb in France with a poverty rate of 45%, three times the national average.

These districts, around only 15km away from the gleaming lights of the Eiffel Tower, the lavish Champs-Elysses avenue, fine art galleries and the ‘chin chins!’ of tourists toasting their Parisian soiree with a digestif along the banks of the Seine, live ‘The Other France.’ The France some would rather not see. The France some choose to overlook.

At times of political convenience - in the wake of a terrorist attack or when another migrant child is washed up on a Calais beach - the Banlieues are prodded and poked and charged the culprit by gangs of far-right politicians. Their loyalty to the Tricolore is a constant topic of debate which has transformed these areas into the concrete powder kegs of hate, race, religion and identity in modern France.

It’s hard to imagine a starker contrast between the Banlieues of France and Manchester, yet its footprints can be found in many places in England’s northern capital. Paul Pogba - the Manchester United starlet and seen as one of the clubs own having played for them at academy level since an early age - was born in the Parisian Banlieue of Lagny-sur-Marne. And Algerian footballer and Manchester City winger Riyad Mahrez is another kid of the projects - born in Sarcelles, north of Paris.

These sportsmen proud of their dual-nationality, a key pillar in the identity debate of the Banlieues, express such heritage every time they walk out onto the pitch in Manchester.

Feelings of abandonment are shared in both areas too. Many in Manchester, and the North as a whole, feel largely forgotten by London in both politics, society and representation. Those of the Banlieues forgotten too by decision makers in Paris – a pattern that has been a constant for decades, much the same as in Manchester.

In two months’ time, France will decide a new president. With the rise of the far-right in French politics, it seems much of France is becoming increasingly impatience with its immigrant population – many of whom reside in the Banlieues.

At such a critical time in French politics, an autopsy of these power kegs is a timely investigation in the age of resurgent far-right leaders, the migrant crisis and the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic.

How did we get here? Why are these areas seen to many as the backwaters of modern France? Can we find the answers to such in the sports and sportsmen of the country?

The Banlieues at the polls

France will vote for a new President in April and the Banlieues will be a closely watched battleground come election day. What will France look like post-election? And will the Banlieues, with their unique makeup, decide what that future looks like?

A 2022 poll carried out by IFOP, the French institute for public opinion, detailed the way the suburbs are expected to vote this year. It seems to suggest that a shift has taken place over the last decade in the Banlieues.

The working classes of parts of these areas are now, more attracted to the right than their historic home of left-wing politics. A trend that has been seen in the UK and America in recent years – with the politics and swagger of Boris Johnson and Donald Trump wooing working-class leftist voters.

The faces leading the right-wing charge in France are Marine Le Pen of the newly-labelled Front National (RN) and Èric Zemmour, media mogul turned chauvinistic grunter - a provocateur who revels in outrage.

Zemmour, fairly new on the political merry-go-round (he only announced his intentions to run in November 2021), has attracted a cult following for his belief in ‘the great replacement’ theory, one of the main ideological pillars to French fascist thought.

The theory dictates that the current Judeo-Christian civilisation will be overrun by a new Islamic universalism and by 2100, France will succumb to an Islamic Republic.

Zemmour has been charged 15 times for inciting racial hatred in the past and in 2020 was charged for labelling young, lone immigrants coming to France as “thieves”, “murders” and “rapists.”

“They have nothing to do here. They are thieves, they are murders, they are rapists. That’s all they are, and they must be sent back.”

- Èric Zemmour speaking in 2020

The 63-year-old denounced the charge as “a stupid condemnation.”

Zemmour is himself the son of Algerian immigrants who arrived in France during the height of the Algerian War of Independence. Plus ça change.

Yet Zemmour is well liked in large swathes of France. And the resurgent face of far-right politics in the country is a trend that has the centre-right incumbent Emmanuel Macron rather worried.

The rise of far-right nationalists may sit uneasily for the residents of the Banlieues – telling perhaps of an increasing hostility and growing impatience with the immigrants of the suburbs. But this doesn’t entirely seem to be the case. The non-priority suburbs – those with a non-immigrant majority - have been a popular base for these kinds of politics in recent times.

According to the IFOP poll, if the voters of the non-priority neighbourhoods were to cast their ballot today, Le Pen would win with 22% of the vote, 6% higher than the national rate. Jean-Luc Mèlenchon, the socialist candidate, would come second with 20%, whereas nationally he polls at 9.5%. Macron third with 15%, 5% down from his victorious 2017 result.

The priority neighbourhoods (QPVs) which are classed as the poorest in France with a high immigration population tells a different story. Mèlenchon would win outright with 37% of the vote yet it is Le Pen who finishes second with 15%.

Over the last decade the Banlieues have been pulled to the extremes of the political spectrum. Since 2012, voting intentions for right-wing candidates in the non-priority areas has risen by 9%, alongside a 13% rise in support for the far-right nationalistic politics of Le Pen and Zemmour.

"There are many white French people who are themselves very poor and live in the Banlieues who are maybe open to the populist interpretation of the National Front."

- Barbara Lebrun, senior lecturer of French cultural studies at the University of Manchester

This is set against the opposite trend seen in the QPVs over the same period. Where support for the politics of the left currently polls at 56%, 46% of which is for the radical left.

But what do the Banlieues, historically feared as the ‘red pincers’ clutching around metropolitan cities, find attractive about far-right politics?

A politics that, with the arrival of Èric Zemmour, has seeped into the territory of teatime fascism (Zemmour has been nicknamed the ‘TV-friendly fascist’)

It is surveyed that their strong showing on matters of security and crime, a constant in the Banlieues, have been a big incentive among a middle-aged and mostly atheist or Catholic support base.

The IFOP poll also states the right can find support in the Banlieues from 54% of workers where they can only find 6% support from managers or professional executives.

The unemployed and workers on less than €894 a year salary have also been attracted to the politics of the right – with 37% of the unemployed and 36% of low-wage workers intending to vote for some strength of rightist politics come April.

Barbara Lebrun on what the 2022 Election means for the Banlieues

The impact of the pandemic also cannot be overseen in dictating how the Banlieues will vote in this election. Many look to Macron with disappointment after he failed to deliver on his promise made in 2017 to tend to the economic divide between French cities and their suburbs whilst also pursuing a COVID recovery plan which exacerbated such divides.

The COVID death rate in the suburb of Seine-Saint-Denis in Paris rose by 62% in March 2020, the highest in France. A death rate allowed to reach such proportions due to the region, home to 1.6 million, having the lowest number of doctors per head.

With 60% of the population in France in 2010 living in highly-urbanised areas of 800 inhabitants per square km, the Banlieues could well decide the 2022 Election where the far-right can rely on strong support from these areas alongside much of the rural population too.

The 2005 Riots

"Get out the car! This ain’t Thoiry"

- Hubert, La Haine (1995)

Occasionally, the wick ignites and violence erupts. 2005 was an example of such. The country saw three weeks of rioting and altercations with Police forces on the outskirts of almost every major French city.

It was not the first riots nor was it the last. The uproar grew so much that President Jacques Chirac was forced to declare a national state of emergency.

A precursor to such violence was seen in the 1995 film La Haine. The suppressed rage and anger felt by so many youths in the Banlieues was cast onto the silver screen and for the first time, youths from the projects had a film that spoke to them.

When the film was shown at the Cannes Film Festival, policemen turned their backs to the cast and crew, feeling the film was little more than an anti-Police polemic.

Matthieu Kassovitz’s picture struck such a nerve in French culture, that instructions for the film to be watched were hurriedly sent around the President’s cabinet in Paris at once. ‘The Other Paris’ was beginning to speak. And decision-makers needed to listen.

The three stars of the film, a North African, a black man and an Eastern European Jew plod round their district disillusioned, angry, upset and in need of excitement. Their confusion when they find themselves in central Paris, almost tourists in their own city, as telling as ever of the divide between the capital and its boundaries.

“Get out your car! This ain’t Thoiry”, Hubert shouts to a journalist and her cameraman filming the trio sat in a children playground. The cameraman, giddy he’s getting a juicy scoop, starts to grin as the characters become restless and begin to hurl stones towards the press car.

“What’s Thoiry?”, Vinz asks Hubert. “A drive-in safari park”, Hubert replies cynically.

"Some mainstream politicians have lubbed together the Banlieues and made it as a general stereotype for social divisions and non-white traditions."

- Barbara Lebrun, senior lecturer of French cultural studies at the University of Manchester

2005 was the manifestation of all these feelings, and then some.

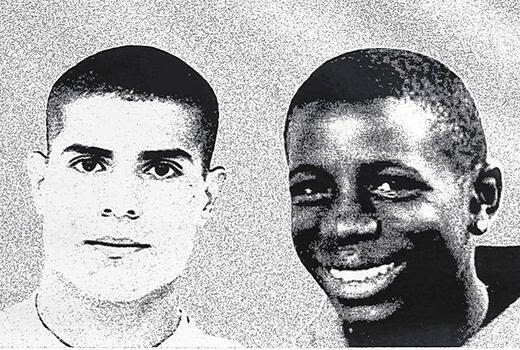

The catalyst was the deaths of two teenagers, 15 and 17, who were electrocuted in an electricity substation in Clichy-sous-Bois, Paris. The boys, Bouna Traore and Zyed Benna, the children of Malian and Tunisian immigrants, were being chased by Police after a game of football.

Zyed Benna and Bouna Traore

Zyed Benna and Bouna Traore

It was Ramadan. The boys were in a rush to get home so they could break their fast and didn’t want to be harassed by Police fearing a lengthy interrogation. The explosion was so powerful that the neighbourhood was plunged into a blackout.

Traore and Benna died of their injuries in hospital whilst their friend, Muhittin Altun who was with them at the time, returned home after spending weeks in hospital being treated for burns.

Muhittin Altun returning home

The Policemen chasing the group of boys were cleared of wrongdoings in 2015, even though the court heard that the Policemen knew the boys were stuck in the substation.

“Police officers are untouchable. It’s not just in this case, they are never convicted.”

- Zyed Benna's brother speaking at the time

The Banlieues were tired of adding another two names to the list of boys killed by the Police.

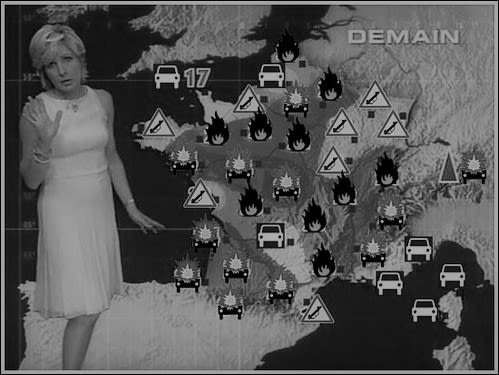

274 regions of France erupted into conflict. 9,000 cars torched and an estimated €200 million worth of damage caused by kids who’d had enough.

Unemployment rates of 15–24-year-olds in the areas that rioted are a clear anomaly compared to the rest of France. 41% in Grigny. 54% in the Banlieues of Toulouse. 37% in Clichy-sous-Bois. 42% in the Nantes projects.

Barbara Lebrun speaks on the 2005 Riots

The state took a hard-line approach. Interior minister Nicholas Sarkozy preferred inflammatory language to describe the rioters, labelling them as “racaille”, a French term meaning thugs or lowlifes that bears racial and ethnic connotations.

During and after the rioting, Sarkozy would often comment how the Banlieues are nothing more than the rat runs for those who deal in drug-trafficking and prostitution.

By mid-November the wounds had still not healed yet Sarkozy announced a wave of deportations for convicted foreigners regardless of whether they had residency in France or not.

He also announced that immigrants seeking residency shall have to master the French language and integrate into society first.

His tough approach was well liked by voters. The press reported an 11-point rise in opinion polls for Sarkozy and two years later was elected President of France. A post he held until 2012.

Les Bleus

"When they win they are Black, Blanc, Beur. When they lose they are immigrants from the ghetto"

- Eric Cantona, French footballer

Football has always been closely woven with politics. Nowhere more so than in France. But it has not always been the favoured sport. Tennis, cycling, boxing and rugby have historically inspired the national spirit more so than football. However the events of 1998 and beyond have questioned that.

The French football team (FFF) has long acted the reflection to French insecurities. The team confronts society with its obsessions of culture and race, politics and identity. And the FFF continues to breed not only footballers of immense talent, but also players with a political and social conscience – proud of the long-demonized Banlieues they grew up in. The inequality of these areas also instils an unflappable determination to ‘make it’.

Barbara Lebrun on 1998 and the relationship between France and its sportsmen

The unique environment of the suburbs has allowed not only players to represent Les Bleus but also play for a host of North and West African teams through their parents or grandparents.

And whether they put on a French, Algeria or Senegalese shirt, they confront the cynicism that ‘Deep France’ have for the boys from the Banlieues when they do it.

These men are the son of immigrants from the long-forgotten backwaters pushed out of sight from the cities of Paris, Lyon and Marseille who represent France at the highest level.

Yet the FFF continue to be hounded by politicians and the media for not being ‘French enough’ or not singing the French national anthem which some believe to be a stain on their character put together in the countries of their parents in Africa or the French colonies.

Kalidou Koulibaly, the Senegalese captain who grew up in the Parisian Banlieue of Saint-Die-des-Vosges commented on the matter. “We are black, white, Arab, Africa, Muslim, Christian”, he said, “yes, but we are all French.”

The racism and hostility the powerful have for the kids from the projects was evidenced in 2011. Then manager, Laurent Blanc and a host of other officials, had secretly approved a ‘race quota’ to limit the number of black and Arab players in the youth system to 30% to make the squad more white and more ‘French'.

It was an ignorant and racist gesture, at a time when the suburbs produced around a third of the national team stock. By now, that figure is even higher. Blanc stood down as first team manager following the comments in a sporting drama reflective of how many in France see those who come from the outskirts.

These kids may be wildly celebrated when they return home with gleaming trophies. Its leaders impatient to jump into the celebratory photos, invite them to their grand palaces and shake their hands to proclaim the social exclusion and economic gulf between themselves and ‘The Other France’ remedied.

Christian Karembeu, part of the 1998 squad, refused to sing La Marseillaise upon finding out his ancestors had been displayed in human zoos in New Caledonia for the pleasure of French colonists. This quiet rebellion infuriated far-right politician and founder of the Front National Jean-Marie Le Pen so greatly that in 1996 he expressed his resentment at the national players who refused to sing the national anthem.

Jean-Marie Le Pen speaking on the reluctance of some French players to sing the national anthem. At the time, the FFF was made up largely from players with immigrant backgrounds

The 1998 squad marked a turning point for the FFF and French society. The team, led by midfielder Zinedine Zidane – who grew up in the notoriously rough Le Castellane Banlieue of Marseille, was hailed as a triumph for French immigrant integration.

‘Black, Blanc, Beur’ was its nickname. Referring to the black, white and Arab faces in the squad that took on the world and won. This team, made up of around 50% immigrant stock, united the country in giving them their first World Cup at a time when the perennial problem of immigrants and their role in France was at the forefront.

After beating Brazil at the Stade de France, chants of ‘Zidane Président!’ was sung all down the Champs-Élysées, with the midfielder’s face projected onto the side of the Arc de Triomphe, a monument to the military grandeur of old France. The icon of new France was now a little boy from the Marseille slums.

"All these things came together to redefine the idea that France was at last confident, satisfied and celebrating its multi-racial identity."

- Barbara Lebrun, senior lecturer of French cultural studies at the University of Manchester

The Arc de Triomphe, an unquestionable symbol of Free France where leaders and generals in the past have stood, chest out, draped in the blue, white and red of the Republic was, in the immediate wake of the 1998 Final, plastered with the face of the son of Algerian immigrants.

The scenes along the Champs-Élysées after the final have been compared to the Liberation of France in 1945 following five years of Nazi occupation. That analogy may have more meaning to it than just the fact millions of joyous faces sung into the night along France’s most famous avenue. It was a brief flicker of liberation for the immigrants and their sons and daughters of France. That a team who had more in common with them, than the usual heads of social architecture, were champions of the world and suddenly, France was in harmony with its citizens, whatever colour.

The pattern continued, and in 2018 the French National team won again, in Russia this time with a team scouted from the Banlieues. Eight of the 23-man squad were born or raised in Greater Paris. That includes Kylian Mbappe, French footballs golden child, who grew up in Bondy where 30% of residents live below the poverty line, more than double the national average.

And all but two of the entire France squad had some form of dual-nationality status making the victorious 2018 team a supposed triumph for French multiculturalism.

It was a true and free rebuttal of the populist rhetoric spoken by politicians and media jackals who believe France is somewhat impure because of their presence.

"Sports is politics"

-Lillian Thuram, French footballer & 1998 World Cup winner

The cruel irony between how politicians and the media treat Les Bleus will continue with no end in sight. It’s something players have experienced and dealt with for decades. The FFF is the pawn for politicians to move at their convenience. Football acting as the vehicle for social change, sincere or not with the national team the mirror to French society.

Constructing the HLMs

"The landscape being generally thankless, they’ve gone so far as to eliminate windows"

- L'amour Existe (1960)

The urban make-up of Paris was first drawn up during the reign of the monarchy. In 1670, King Louis XIV built a grand city wall around Paris to aid in the collection of the much-hated octroi tax, a levy on goods coming into the capital.

Consequently, a lawless outback of crime and forbidden goods untouched by the octroi grew outside the city walls. This land was soon populated by ‘Rôdeurs de Barrière’ (Barrier prowlers) who would hide in hedgerows and steal from anyone who came close.

“It was an inhabited location where there was nobody, it was a deserted place where there was somebody. It was a street in Paris that was wilder at night than a forest, gloomier in daylight than a graveyard.”

- Victor Hugo, French novelist (1802-85)

By 1841 the city walls had expanded. Yet it was met with confusion by residents. One illustration from the time depicts a man and woman standing surprised outside their hut, looking over to the grand palaces of Paris in the distance and asking, “So we’re Parisians now?”

This shows the clear indifference those on the outskirts of Paris felt about the capital they were now all of a sudden clubbed together with. An indifference which is still there today among the concrete Banlieues when its residents look towards the capital. Are they Parisian? Because most of the time the suburbs feel like an entirely different country.

"What you need is probably a lot more cash injection - a redistribution of national wealth - and it takes a particularly brave political party to advocate for that, usually from the left."

- Barbara Lebrun, senior lecturer of French cultural studies at the University of Manchester

By the start of the 20th Century, the outskirts had become a catchall slum for all things crazed and curious.

But thirty years on, it was clear something needed to be done about them.

The HBMs (habitation bon marchè or "cheap housing") started construction in 1928. Nearly 300,000 low and medium cost housing sprung up. Uniform in price, colour and design, and equal in their ability to sap the spirits of its inhabitants.

Yet on the eve of war in 1939, there was still no substantial answer to social housing for the projects. The population of the suburbs was now equal to that of Central Paris and it had become a hotbed for communist politics among a working-class population.

Paris needed to do more for its ‘Red Belt’ and so by 1950 the city decided - hastened by a fear of communist revolt (some in Government referred to the Banlieues as the pincers gripping around Paris) and partly to house the vast numbers of workers arriving from Africa and the French colonies to help rebuild the country after wartime, developed a wide-ranging system of HLMs (habitation à loyer modéré or "reduced-rent housing").

The strategy here is the one we see today. Up and up again! Grand uniformed high-rise apartments doused in grey concrete inspired by Le Corbusier's model cities of the 1930s.

Today, these buildings can look oddly dystopian. The footprints of a highly-stylised social housing project now decaying. No more so dystopian than the Banlieue of Chanteloup-les-Vignes, south of the capital - the filmset for the 1995 film La Haine.

Here the town square is lined with giant frescos of French culture figures like Charles Baudelaire and Arthur Rimbaud. A rather queasy, almost Orwellian state-sponsored attempt to corral the largely immigrant population around the French culture and hack them into shape of a France “singular and indivisible.”

Conversation with Barbara Lebrun, senior lecturer in French cultural studies at the University of Manchester

Lycées (secondary schools) grew also across Paris, but only for parts of the city. By 1960, Central Paris had 29 of these schools. The Banlieue area, with a population nearly double that of Paris, had only nine.

Education inequalities between Paris and its neighbourhood have not gone away and today many opportunities remain a mostly closed door for those of the Banlieues.

A 2016 report concluded a 30-year-old man with a master’s degree from a ‘priority neighbourhood’, a suburb at the bottom of the rung, was 22% less likely to secure a managerial job than his equally qualified peer from another area.

Another report from 2015 concluded someone with a name presumed to be Muslim or North African is four times less likely to be hired.

These areas are also stunted in limbo due to poor public transport links.

The 17km route from Clichy-sous-Bois to the centre of Paris would take someone 90 minutes on various modes of transport.

It’s the same for Les Ulis, southwest of Paris, where there isn’t even a train station.

Picture accredition

The Banlieues at the polls - "Marine Le Pen, Leader of the French National Front" by theglobalpanorama is marked with CC BY-SA 2.0.

"File:Le Pen Paris 2007 05 01 n2.jpg" by Marie-Lan Nguyen (User:Jastrow) is marked with CC BY 2.5.

"Image" by Nocturnales is marked with CC BY-NC 2.0.

Constructing the HLMs -"Noisy-le-Grand: McDonald's Arcades" by harry_nl is marked with CC BY-NC-SA 2.0.

"Place Martin Luther King - maintenant condamne // Martin Luther King Plaza - now condemned" by t-bet is marked with CC BY-ND 2.0.

The 2005 Riots - "cap109" by cwangdom is marked with CC BY-NC-SA 2.0.

"DANGER OF DEATH" by t-bet is marked with CC BY-ND 2.0.

All other photos were attribution free - with thanks.