Is it possible to survive seven days without a smartphone?

UK ministers are considering banning the sale of smartphones to under-16s, but just how hard is it to function with a phone that can only call and text?

I traded my iPhone for a Nokia brick to find out.

“It’s not for a burner phone,” I blurted out to the bewildered store assistant. As if someone actually wanting a burner phone would brazenly walk into EE to purchase one.

My efforts were futile anyway because the most basic, brick-like device EE could offer turned out to be a jazzy-looking flip phone which still had WhatsApp and would leave me £89.99 lighter.

“I’ll just take the Pay As You Go SIM, please.”

And so, somewhat ironically, I ended up resorting to Amazon Prime to find my temporary ‘dumb phone’ - a non-touchscreen device usually without internet or apps.

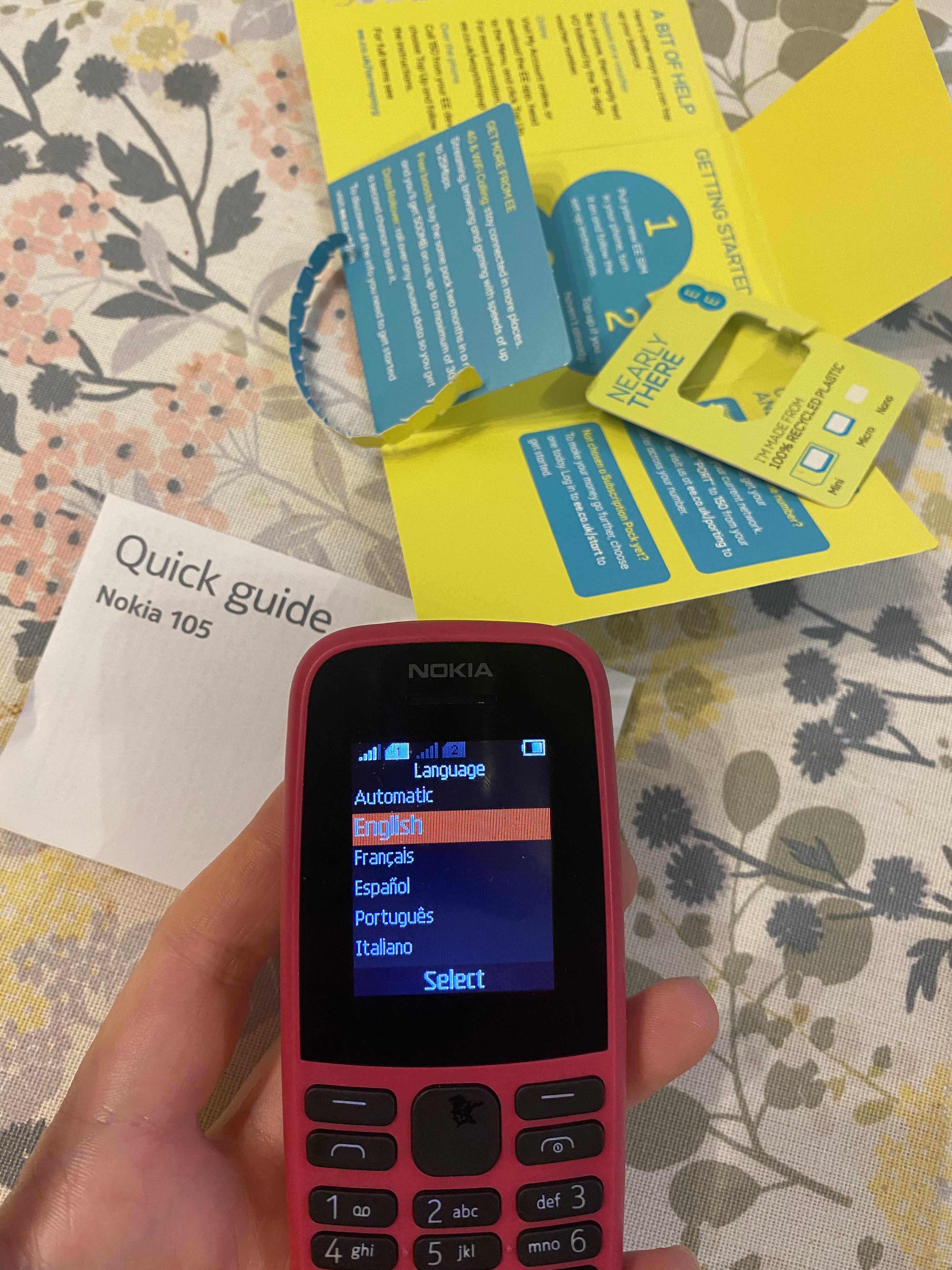

I’m not sure what I expected for £20, but when my Nokia 105 arrived, it really was quite… basic. Not to mention tiny.

If you threw this thing at a wall, the wall would almost certainly come off worse.

My iPhone 11 next to the Nokia 105

My iPhone 11 next to the Nokia 105

One reviewer, who had left a generous five-star review, simply commented: “Cheap and cheerful burner.”

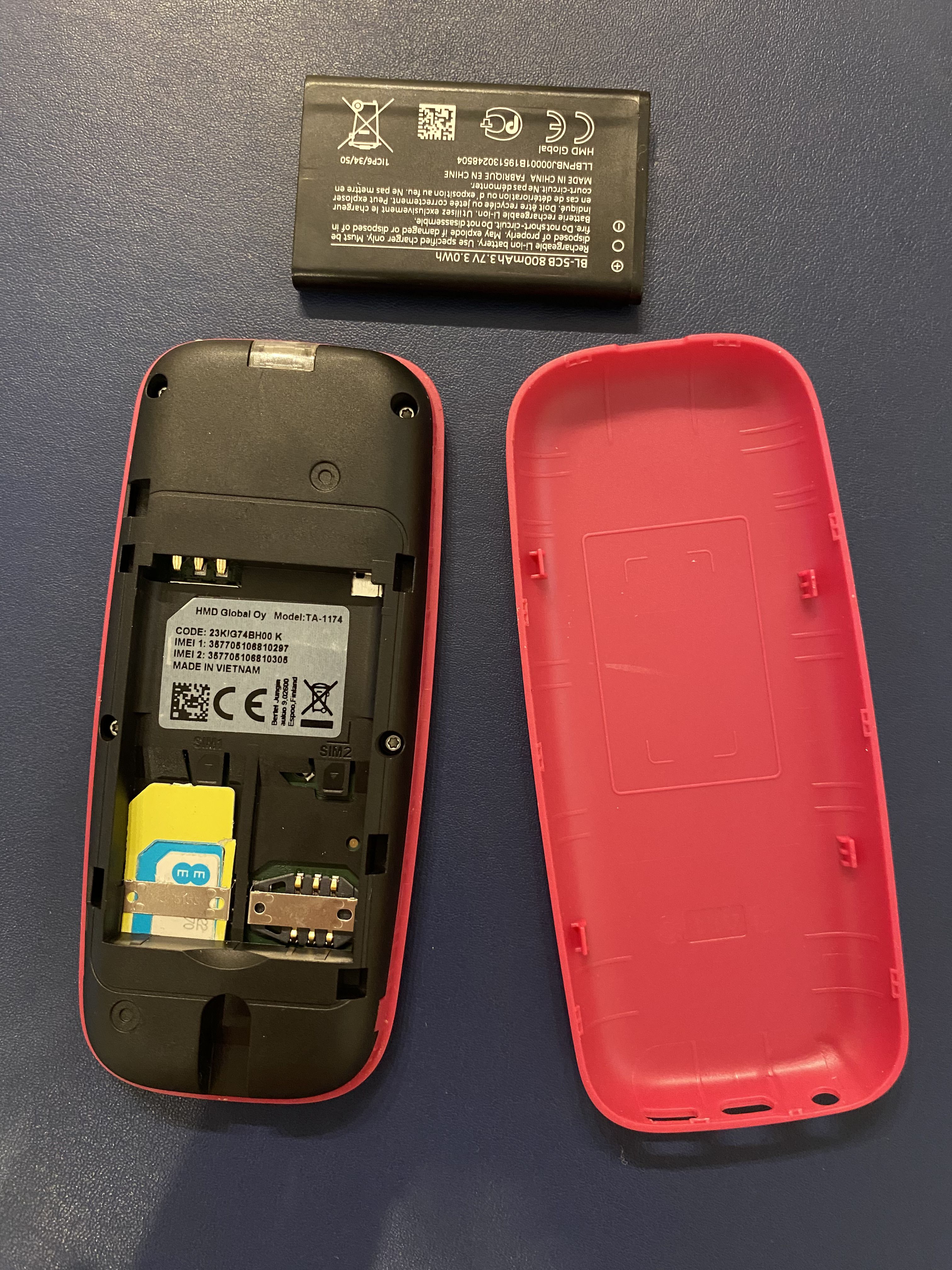

Inserting the SIM, though, was like performing open heart surgery.

As basic as this phone is, it has space for not one but two SIM cards, and unlike a regular smartphone SIM, it needs to be carefully trimmed down to size.

The anatomy of a Nokia brick

The anatomy of a Nokia brick

Once this painstaking task was complete, I was ready to go. Seven whole days without my smartphone. Scary stuff. I could barely remember life before my iPhone, which is quite alarming really.

Earlier this year, the government published new guidance on prohibiting mobile phones in schools, and shortly afterwards came the news that UK ministers are considering banning the sale of smartphones to under-16s. Unsurprisingly, a media storm followed, with both children and adults joining the debate.

What struck me about these discussions was that it seemed to be smartphones or nothing. Even the government guidance refers to “mobile phones and other smart technology with similar functionality to mobile phones”. What about basic mobile phones, like the one I had when I was 11? Is it even the actual devices that are the problem, or the social media apps on them?

With this in mind, I decided to see what seven days without a smartphone was like and whether my iPhone could be replaced by a humble Nokia brick - like the one I had at school.

Setting up my phone for the week

Setting up my phone for the week

A built-in flashlight to rival any smartphone

A built-in flashlight to rival any smartphone

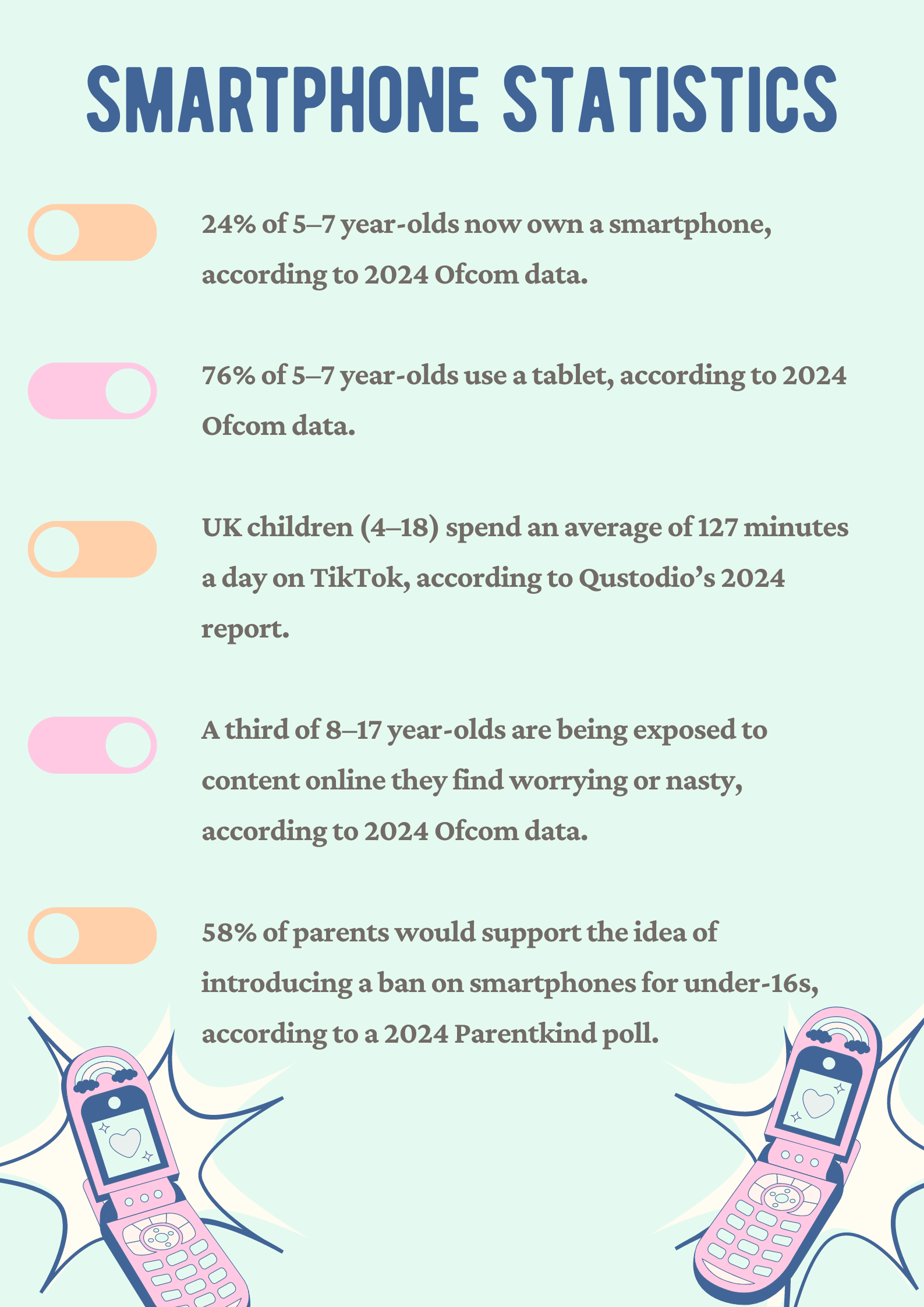

Nearly a quarter of UK five–seven-year-olds now own a smartphone, according to Ofcom's latest data.

So, what is the impact of introducing children to screens so much earlier?

“We're creating a world of zombies, where people need stimulation all the time. It’s bad what it's doing to the brain and how it's impacting our neurocircuitry,” says Dr Charlotte Armitage, a psychologist and psychotherapist.

She says colleagues who work in neurodevelopmental services are “overwhelmed by children who have developmental delays as a result of overusing screens and devices”.

Dr Charlotte Armitage is a psychologist specialising in the impact of device use / Credit: Rhian Hughes

Dr Charlotte Armitage, who specialises in the impact of device use / Credit: Rhian Hughes

Armitage, who founded No Phones at Home Day last year, says introducing smartphones early in life, even through parents’ use, infiltrates key developmental milestones, like “pincing” - the act of pinching your forefinger and thumb for tasks like holding a pen or knife and fork.

“Unfortunately, that pincer grip has been affected because we are tapping. There is not enough tangible play with real-world objects,” Armitage explains.

Does my experiment count as “tangible play with real-world objects”? Because it certainly didn't involve any tapping. Writing even a short message took approximately three to five working days and involved a level of problem-solving I had not anticipated.

It made me realise how incompatible our modern texting habits are with brick phones. My friends were sending me streams of sentences, not understanding that, with the brick, I had to exit what I was typing to read another message — sometimes a single word — and start the process all over again.

It doesn't surprise me that young people receive an average of 237 notifications a day, according to a recent study by common sense and C.S. Mott Children's Hospital.

The arduous texting process on the Nokia made me much more inclined to make a phone call rather than send a text.

Smartphone stats at a glance

Smartphone stats at a glance

Interestingly, though, my Nokia struggled to make or receive calls, which, thanks to the helpful man on the Tesco phone kiosk, I discovered was because this device runs on 2G, which is now supported by fewer networks.

It meant I had to use the actual landline to call people, which I ended up not minding; it felt much more intentional.

Usually, people my age (I'm 24) are against the idea of phone calls, instead preferring a text or voice note. I think because we're so used to messaging and emails, making or answering a call seems significant, and suddenly there's pressure attached to it. Even if it's a family member or friend, I'm inclined to think something bad has happened if they're ringing.

And I'm not alone, with almost a third (32%) of Gen Z rarely making a phone call, and a fifth (20%) finding it weird when they receive one, according to research by Sky Mobile.

Young people have taken to TikTok to poke fun at their phone anxieties

I found the first few days with the Nokia quite anxiety-inducing, and my regular FOMO (fear of missing out) was heightened.

What was everyone planning on WhatsApp? What had I missed on Instagram and TikTok? What would people think when they saw I hadn’t posted a BeReal for seven whole days?

Scott Lyons is a National Education Union District Secretary for Norfolk. He says social media, vaping, and poor parenting have culminated in “a perfect storm” for schools.

Scott Lyons is an NEU District Secretary for Norfolk / Credit: National Education Union

Scott Lyons is an NEU District Secretary for Norfolk / Credit: National Education Union

Lyons, who also taught for many years, says five years ago, a few primary school-age children would have a phone, but “now you regularly have Year Three children bringing smartphones and handing them in”.

Echoing Armitage’s sentiment, Lyons says schools are seeing a “big issue coming through” with developmental delays. Nursery and reception teachers, he says, are doing more of the children’s intimate care “because they’ve just been parented on a screen".

Scott Lyons on the "huge dopamine, social, and biological changes" schools are facing thanks to smartphones

Scott Lyons on the "huge dopamine, social, and biological changes" schools are facing thanks to smartphones

Elsewhere in secondary education, Lyons highlights a prominent issue in tandem with social media — the continued growth of vaping cultures — which relates to phones “because TikTok videos, which give them a 15-second dopamine release, are very aligned with the vaping nicotine release”.

Children spend an average of 127 minutes on TikTok per day, according to research by Qustodio.

Looking back, I’m so grateful social media was only just beginning when I was at school. Facebook — the social media platform of my teenage years — was a contentious topic in my household.

“But everyone else has it,” I’d moan to my mum when she refused to let me get an account before I was 13.

In 2023, 30% of parents agreed they would allow their child to have a social media profile before they were the minimum age the app/site required, according to Ofcom’s latest data.

Fair play to my mum. She stuck with her decision, and it wasn’t until my 13th birthday that I sold my soul to Mark Zuckerberg.

I remember sitting at our family computer carefully selecting my profile picture and posting a ‘status’ to tell this virtual world I had arrived.

Molly Forsyth, 30, from Birmingham, swapped her iPhone for a Nokia brick (coincidentally, the “cheap and cheerful burner” 105) in 2020 when she felt overcome by its distractions.

Impressively, she managed it for nine months, making my seven days seem measly in comparison.

Forsyth, who works in marketing, ultimately returned to an iPhone “because too many complications kept arising with the willingness of people to meet you on your level”.

My friend told me it “had been an effort” to keep me in the loop while making plans during my experiment.

While Forsyth wouldn’t go back to such a basic phone, she says the time away made her relationship with her smartphone much healthier.

“If some people actually stepped away for a while and went back, they would realise that it's worth trying to limit it and be really mindful with how you use the device because they are such powerful things,” says Forsyth.

While some of her friendships weakened because people didn’t reach out, Forsyth says others strengthened.

“When you limit your technology and how accessible you are to people, the more meaningful interactions are with them if they want to reach out to you,” she says.

Forsyth’s housemate lived in a different city during the pandemic, and when she used the brick, they went from messaging to regularly speaking on the phone.

Molly Forsyth managed to stick with the Nokia for nine months

Molly Forsyth managed to stick with the Nokia for nine months / Credit: Own

Meaningful connections aside, how did Forsyth navigate the practical stuff?

Planning, she says, was key - printing out train and event tickets, and saving taxi numbers.

“Once I got accustomed to that, it is really not as scary as you would think it would be,” she says.

I agree - the world didn’t end because I had to print my parkrun barcode instead of scanning it on my phone.

However, running without music was difficult.

Forsyth coped by purchasing a “really basic MP3 player”, which she says also made her consider “how we have become so reliant on algorithms to help us find new things to enjoy”, including music and films.

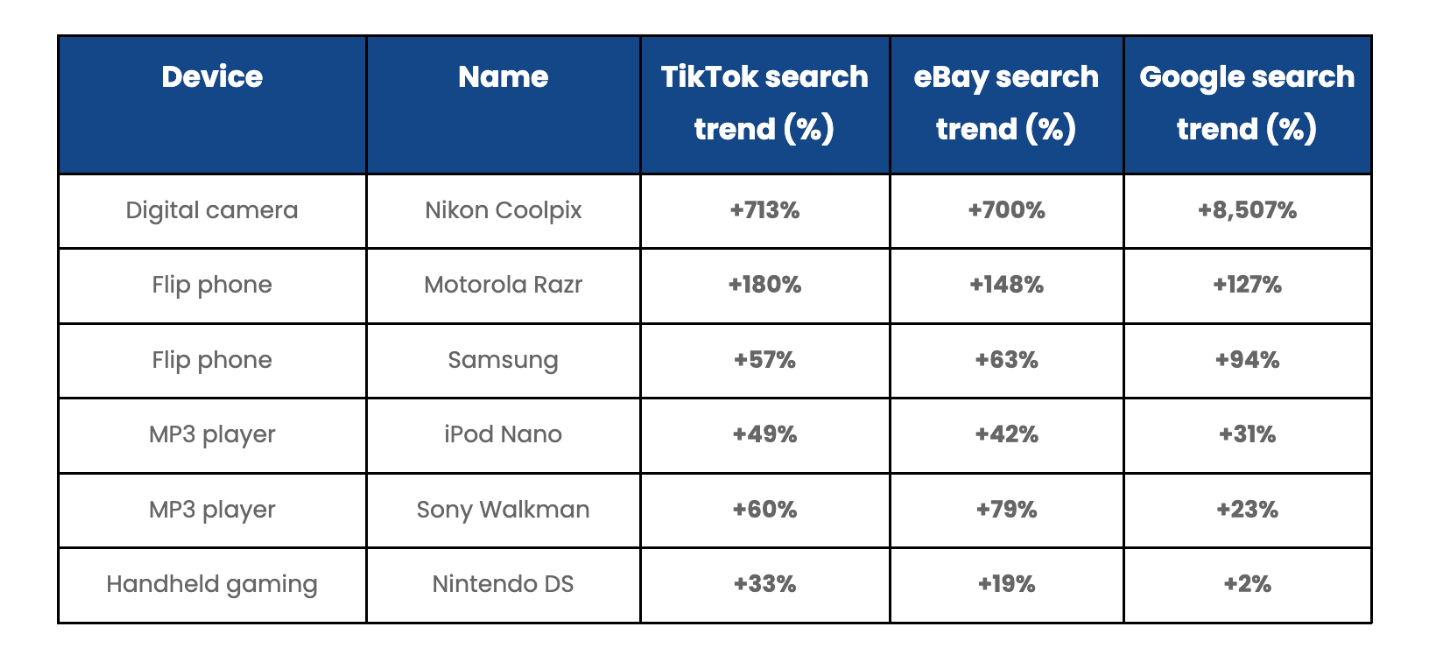

Driven by the Y2K trend seen across the fashion industry, Gen Z does seem to be seeking ‘vintage’ tech, including digital cameras, MP3 players, and flip phones.

eBay searches for the Motorola Razr, a popular 00s flip phone, increased by 148% in 12 months, and TikTok searches for the iPod Nano were up 49%, according to data compiled by refurbished tech and media experts at musicMagpie.

Data compiled by refurbished tech and media experts at musicMagpie shows a huge demand for so-called retro-tech / Credit: musicMagpie

Data compiled by refurbished tech and media experts at musicMagpie shows a huge demand for so-called retro-tech / Credit: musicMagpie

But is it anything more than an aesthetic trend?

Liam Howley, musicMagpie’s chief marketing officer, says while “the expectation of being constantly connected and contactable through your phone” has potentially prompted people’s interest in simpler technology, there’s likely a “nostalgic element” at play.

“For a lot of younger people, simple, noughties mobiles are being purchased purely for their nostalgic appeal – for the aesthetic of the blurred camera and a hot pink flip design reflective of that time – rather than to be used as a full-time mobile phone,” says Howley.

Whipping out the brick in public was actually kind of embarrassing and I don’t know why. Maybe because it was so ridiculously small? Whenever I met up with people, it was passed around like an artefact, rather than a functioning device.

Because of these reactions, I felt a bit self-conscious using it in public. One friend asked me: “Do you have to top it up? Is that still how it works?” as if Pay As You Go was a distant thing of the past. The same friend, who is a hardcore voice note fan, quipped: “Exciting - I’ll have to text you,” like it was an extinct art form.

Honestly, I did not miss the voice note thing. Sometimes, I like receiving personal podcast episodes from close friends, but for the most part, they are impractical. You can’t really hear them outside, and it’s awkward on public transport if you don’t have headphones with you.

Despite her positive Nokia experience, Forsyth says she wouldn’t return to it because of practical tools like GPS and banking.

At one point during my experiment, I nearly had to abandon my shopping at the self-checkout when I got PINs mixed up, clearly signalling my overreliance on Apple Pay. Barclays recently reported that 93.4% of all in-store card transactions up to £100 were made using contactless.

When we went out for my friend’s birthday, I had to steer them away from a restaurant choice which required a smartphone to access the menu and order food.

At the pub, there was one moment when everyone at the table was looking down at a screen (no shame. I’m usually the same), and I genuinely considered a quick game of Snake on the Nokia.

So, when does device overuse become an addiction?

“I would say that a lot of us are very addicted to our devices,” says Armitage.

She adds: “You don't have to be physically addicted to something, you can be psychologically addicted. It releases dopamine, that is what creates these addictive mechanisms.”

Connor Jewiss, a tech journalist of more than seven years, says he deletes and hides social media apps on his phone so they are less accessible.

However, he adds: “There aren't many ways to effectively block social media without taking more drastic errors.”

Ultimately, Jewiss says: “Kids don't want to stop using Instagram as they will miss out, and that might affect them in real life in their social circles. The same goes with adults, who might turn to social media out of boredom or habit.”

I definitely turn to social media out of boredom. I physically noticed this with the brick when I’d go to pick it up for no particular reason, only to realise there was nothing to scroll.

The time without my smartphone made me realise I only really need a small circle of contacts. The other stuff — the strangers on Instagram and TikTok — is extra noise.

Often, I forget what I’ve even gone on my phone to do because there’s so much at my fingertips.

And for many young people, it's too much temptation. According to government data, 29% of secondary school pupils reported using mobile phones when they weren’t supposed to in most or all lessons. Government guidance published in February says schools should ban mobile phones but will continue to have autonomy on how they do it.

But what does this mean in practice for teachers and schools?

While schools retain autonomy, Lyons predicts some schools will move towards “a very hard behaviour model expectation — schools a bit like the Michaela School — where it's zero tolerance, no-nonsense behaviour, and there'll be no phones, no devices”.

Schools on the other end of the spectrum, he anticipates, will deliver “trauma-led, trauma-informed education” focused on “therapeutic recovery”.

Scott Lyons predicts schools will move towards more extreme measures

Scott Lyons predicts schools will move towards more extreme measures

In the current climate, Lyons says: “We are asking schools to do more, to be mental health hubs of the community, to be the social tech overlords, but the government has just given them less money.”

He says action also needs to come from a community-led, bottom-up approach.

“We've got the power in our communities to decide how to do this, but we're going to have to negotiate, we’re going to have to compromise, we're going to have to talk to one another,” he says.

Lyons says he knows of a south London primary school community that has collectively refused to buy their children smartphones until they get to Year Six. And even then, a subsection has committed to buying their children Nokia bricks rather than iPhones.

So far, it appears to have successfully removed some of the peer pressure surrounding having phones so young.

This Parentkind survey of 2,496 parents of school-age children in England revealed that 58% of parents believe the government should ban smartphones for under-16s.

“I understand the impetus for a ban. I'd love to go yes. Just ban it, ban it all,” says Armitage.

However, she adds: “If you ban kids from doing something, they are likely to find a way to get to that thing.”

Perhaps schools should hand out cheap and cheerful burners rather than £300 iPads?

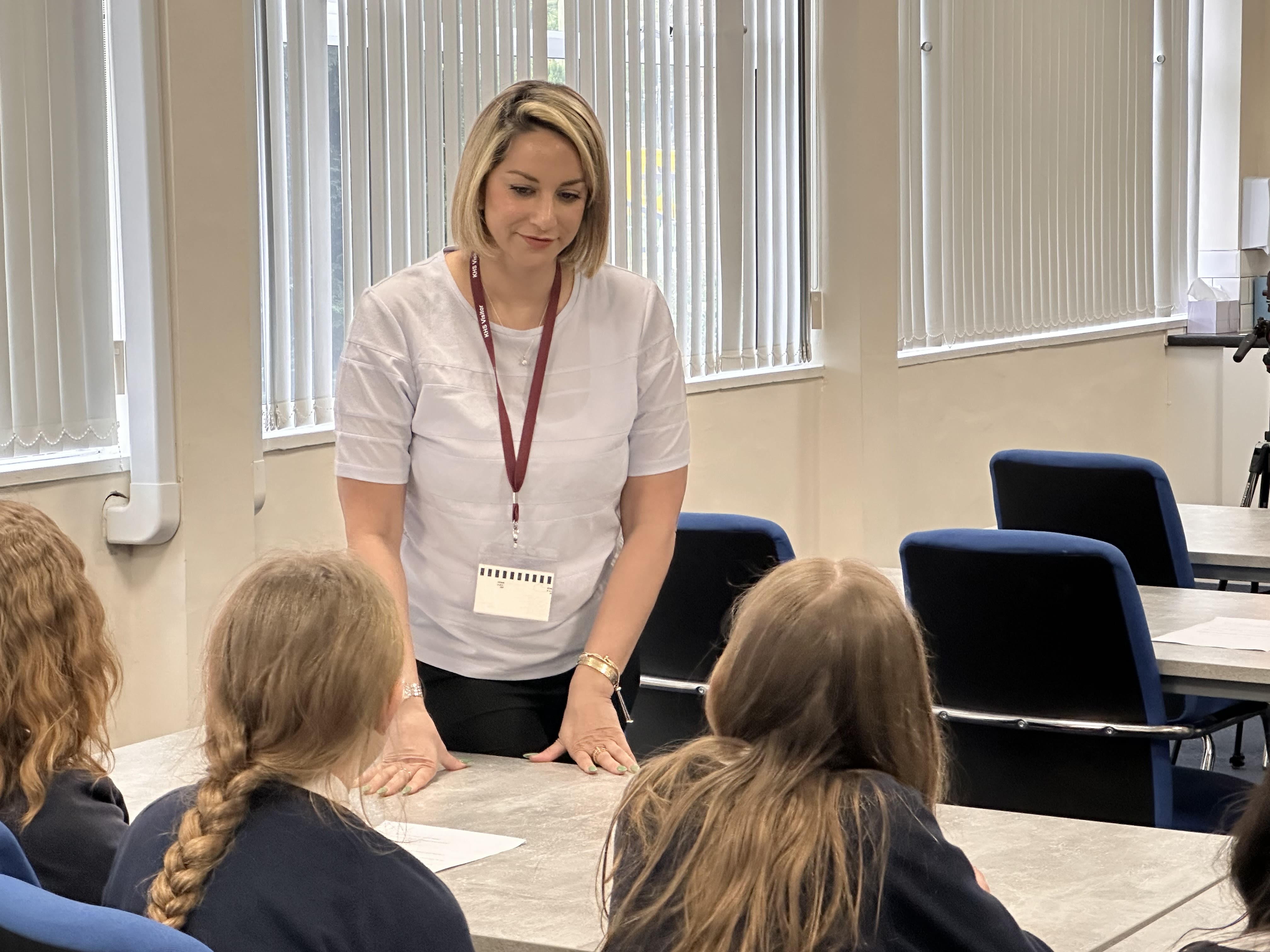

Dr Charlotte Armitage delivering an intervention on device use in a school / Copyright: Own

Dr Charlotte Armitage delivering an intervention on device use in a school / Copyright: Own

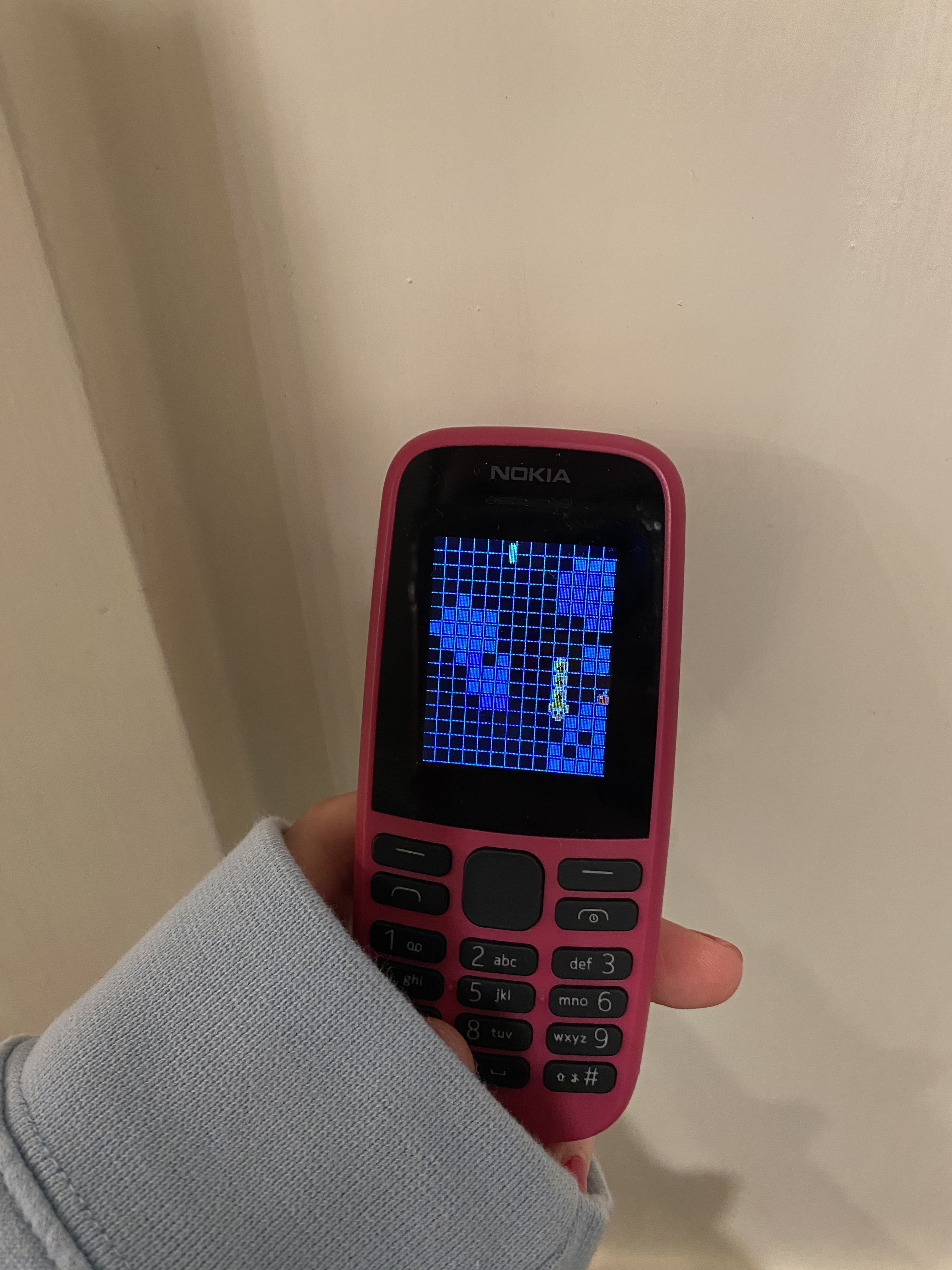

Game of Snake, anyone?

Game of Snake, anyone?

Mine is back in the drawer for now, but even just one week without my iPhone has made me more mindful of its powers.

By the end of the week, using the Nokia felt more liberating than anxiety-inducing, and I felt more productive and focused.

My friends still texted me, sometimes making more effort to check in, and it made me realise people will always reach you if they need you.

There were some practical downsides. Devastatingly, I lost out on Tesco and Co-op points because I don’t have physical loyalty cards, and it was annoying not having instant banking access.

Like Forsyth, I wouldn’t go back to such a basic phone full-time, but I’d consider using a slightly more advanced feature phone - a basic device with modern features like Maps and WhatsApp.

Smartphones might be practical.

But life without them is much simpler.

Simpler phones call for simpler times / Credit: Tom Holmes Art

Simpler phones call for simpler times / Credit: Tom Holmes Art