Escaping Ukraine

Fleeing from danger... into the unknown

The shots began at 5pm. Mira was supposed to evacuate the city that afternoon, but as blasts rang out in the crisp winter air, she knew she wasn’t getting on a bus. Neither were her children.

She tells her story chronologically and without frills, fanfare or fuss – this was the day; this is what happened.

Day one - February 24. Russian troops invade Ukraine. Mira knows she has to leave her town of Sumy with her two children, but transportation is shut down until March 8.

“Soldiers had already occupied my town, and we couldn’t leave the city, no matter how much we wanted to,” she explains.

Day 12 - March 7. An unexpected ceasefire is announced between 9am and 9pm to allow foreign students from India and China to evacuate.

By chance, Mira had agreed months earlier to host two of them. It was an inconsequential decision at the time. Now it could mean the difference between shelling and safety.

Around 12 buses leave between 10am and 11am, with more than 30 ready to follow. Their destination is Poltava, Central Ukraine. Safety. Mira is set to get on one of them with her two-year-old and 11-year-old that day.

But while Mira’s family and the students are preparing to board, a new directive echoes from the shadows of a Moscow citadel. Instead of an evacuation west, Russia is proposing an evacuation to Belarus. Ukraine rejects, and Mira becomes embroiled in a human tug-of-war.

By evening, the ceasefire collapses and the evacuation corridor comes under shelling. Buses turn around. Mira wasn’t even able to get near one – back to the shelter.

“On the night of the 7th of March, they started to shell residential homes," she said. "Twenty-two people died.”

According to Ukrainian reports, this included two children. Mothers grip their babies just a little tighter that night.

"We had to wait for the shelling to end. We waited, and we waited, and the shelling just continued," says Mira.

Day 13 - March 8. It’s morning, and they try again. An anxious crowd mills around, weighed down by more than the layers of clothing and heavy bags they carry.

It’s afternoon, around 3pm, and Mira and her family are on a bus.

But the relief doesn’t come. Would the operation collapse again? Would they be forced to turn back, or – if shelling didn’t just hit the road this time – were they getting on a convoy driving straight to their deaths? They hear the news from Mariupol, where evacuation after evacuation failed as civilians were shelled.

But this time, for Mira, the ceasefire holds.

They travel to a shelter in Poltava – more than 175 kilometres away – through Holubivka, Lokhvystia, and Lubny. On the highway, they pass abandoned cars riddled with bullet holes, doors ajar. Their passengers won’t be coming back for them.

When they arrive in Poltava, the option is brought up to stay there– it’s west enough, it’s safe enough, and people are tired.

Mira, nagged by a sense of foreboding, gets on a train west with her children, and by now, her mother-in-law. A few weeks later, she'd hear on the news reports that missiles have struck Poltava and its surrounding regions.

Mira travels by train from Poltava to Lonya, Hungary, across the Beregcsaba checkpoint. Another 1,500 kilometres.

If she is relieved to cross the border, she is too drained to notice.

In Lonya, they stop for food and rest at a makeshift refugee centre, and then travel by bus north to Zahony – 20 kilometres. A train takes them from Zahony to Budapest. Never-ending – 335 kilometres.

They arrive – and a few days later, Mira is volunteering.

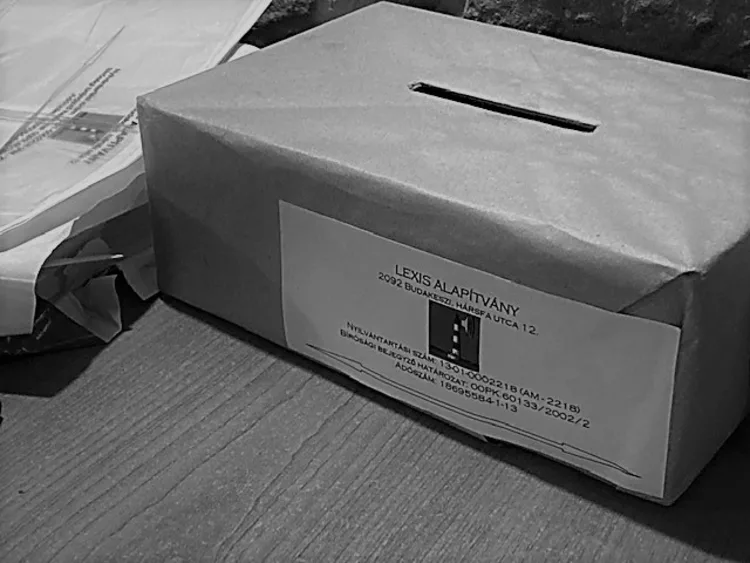

She has come to the Lexis Foundation for Ukrainian Refugees, which was launched by Tatyana Vamos when the humanitarian crisis started. The other volunteers are also women who fled the war, and the foundation ties them all together.

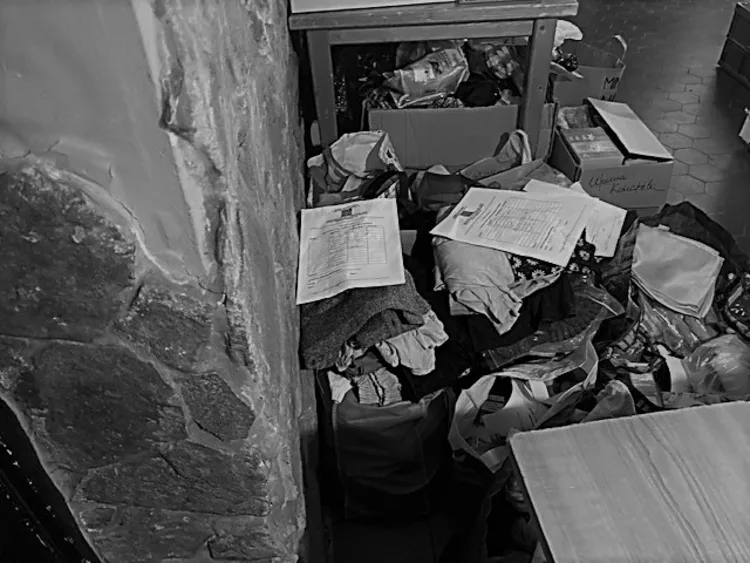

At Lexis, Mira hands out food and supplies to refugees like herself. Currently, she is packing shoes into boxes. They’re children’s shoes, for children who will continue to grow even as their lives stand still.

Mira's journey took five days. It can be done in under two.

Data taken from UNHCR

To lie about the death of a pet – the dog has gone to live on a happy farm – is one of the oldest tricks in the parenting book. But what could Yulia tell her daughter?

The young girl – she can’t be more than six – peeks out from behind her mum’s leg with a shy smile before her head disappears again. Little fists grip a lollipop, a newfound treasure from the cardboard boxes stacked along the basement wall.

What’s your favourite flavour?

She says its pink.

Yulia came with her daughter and son to Lexis for food and supplies. She is slight in stature and her short hair frames a tired smile, but she knows what she wants.

She wants to survive. She wants her children to survive. She needs her children to survive.

Yulia made the decision to leave the Zaporizhzhia region on the first day of the invasion.

The south-eastern area is known for producing heavy industrial goods - and hosting Europe's largest nuclear power station.

It was never going to be left alone.

Shelling began on February 27. By late April, 70 per cent of the wider region was under Russian control.

Yulia packed the children in a rush, but the family only arrived two weeks ago.

“I took the kids and left the city quickly when the shelling started," she says. "We came for a long time as we travelled from city to city. From Zaporizhzhia to Berdiansk, back to Zaporizhzhia to Kropynytsky to Vinnitsia.

"But my mum and grandmother stayed behind. So we were looking for them, waiting to be able to get in touch again, because we couldn’t reach them for a long time.

"With the help of volunteers, we travelled by train and by car and by foot... it's difficult in Ukraine, because there are many cities that are closed completely."

The wait meant Yulia and her two children inched their way across war zones for a month and a half.

“My only thought was that we stayed alive,” she says.

“Our house burnt down from missiles, and my parents’ house blew up too after the shelling – so we have nowhere to go.

“A lot of our friends have already died because they stayed behind. Others are missing –”

An interruption. Gentle tugging on her pantleg and a young voice from knee-height calls for her attention with urgency.

Someone has given her daughter a sticker book – also pink – but she needs mum’s permission to accept. Yulia reluctantly approves - “but thank the nice ladies.”

She is only six – she doesn’t understand what is happening yet, says Yulia.

“She keeps saying we left the cat at home, asking when we’re going back,” she explains.

“Her brother – he’s older so he understands that there’s nowhere to go home to. He cannot reach people from his school – many have died. We cannot find over half of his classmates – we don’t know if they’re alive or dead... they stayed behind and the school blew up.”

The children study in English at home most days of the week and go to a free Catholic school on Saturdays.

Can they find moments of happiness in their days?

“Not yet,” Yulia says. “We cry – we’ve not calmed down yet.”

The future is uncertain for Yulia. They’re here for now, until they can go home – maybe tomorrow, maybe next week, maybe a little later.

Maybe the cat will be there, waiting in the windowsill, when they arrive.

“It will be okay,” one volunteer jokes.“Just speak slowly, and no crying."

But her advice seems to be an imperative for the women at Lexis. If eyes fill with tears, they never let them fall.

Yana fled with her two children from Dnipro. The city may have been destroyed by airstrikes, but Yana is still here. And sometimes, she smiles.

“We left before the shooting started – so the children are more stable because they didn’t experience the fire,” she says.

The girl, nine, attends a voluntary school in Budapest run by Ukrainians; the boy plays football.

Yana herself doesn’t stay still for long – the others describe her as very active – and she volunteers with Lexis every day to organise donations.

She tries to describe her thoughts when war broke out, but she says words aren’t enough.

“Shock and disbelief – horrified at what happened, at what will happen next,” she says.

What will happen next?

“No idea. No plan. Every day, we just hope we can go home tomorrow. We live for today only.”

Yulia doesn’t know what’s next either.

“The question is a permanent one. We’ve not been here long – and we don’t know what’s next.”

Mira just laughs.

Vadim is tired. No. Exhausted.

He came to Budapest 10 years ago to study a master’s degree. He planned to return to Kiev after his course but stayed when the Crimean war broke out in 2014. Looking back now, it may have been the right decision.

“It’s sad to think about it, because in 2014, Kiev was coming up – it was better to live there than in Hungary,” he says.

But now, that optimism seems like a wistful what-might-have-been if shelling didn’t irreversibly change his family’s life in Kiev on February 24.

“I woke up early on the 24th – I don’t know why, I just woke up at around 7am. And I had a message from my mum – war has broken out.

“After 2014, no one used the word “war” – we used terms like “armed conflict”, or “regional conflict”. But this was in Cherkasy, in the middle of the country – I knew this was something else. Soon enough, news came of bombs, rockets, close to my hometown.

“My first thought was – well, I didn’t know what to do with my mum. Should I bring her here, should I not – where do I start?

“After my mum’s message, I hung on the news, and I heard Putin’s message on the night of the 23rd, where he talked about demilitarisation and denazification. I knew it was all a lie."

People like Yulia, Mira and Yana have fled to Budapest, and Vadim is part of a team at Lexis that works tirelessly to help them when they get there.

There are three categories of people who come to Hungary, he reckons.

The first category are people who intended to come here, who have relatives or friends here, and who have opportunities here.

“I would say this accounts for around 15 to 20 per cent,” he says.

The next category are those who want to travel further, generally speak more languages and have plans in place to go west. “The easiest category,” Vadim labels them.

The third category, he says, is the hardest to face.

“They’re the ‘hopeless’, let’s call them,” he explains.

“They don’t know what to do, how to do it. When you meet them, there’s an indescribable feeling there – the possibility that you’re the first, and maybe the last, person who can speak to them in their own language, who can understand them.

"They collapse onto your shoulders, crying.

“It's difficult with them because you try your best to help, but their stay here will just become harder and harder. These are the people who have already lost someone, or whose homes were already destroyed. And it will only get harder for them.”

Vadim, the foundation's IT whizz, prefers to work remotely, dealing with logistics and technical issues.

“I'm not good at emotional support, I don't handle it well,” he says.

He says everyone is waiting for the end of the war, ready – rushing – to go home. But many escaped from the east – and they have to accept that their homes may not be there anymore.

“They want to go back,” he says, “but those people don’t have anywhere to go back to.”

Tatyana Vamos apologises for being late – she’s been up since 6am and she hadn’t had time to eat breakfast, so she grabbed something now. It’s nearing 2pm.

“English, Hungarian or Ukrainian?” she asks.

Born in Zakkarpatia just seven kilometres from the Hungarian border, she grew up speaking Ukrainian and Hungarian. She lived in England for six years before moving to Hungary a year ago, so she’s fluent in all three.

The mother-of-two worked for an American company based in Kiev, but the war has left her without a job – and without words.

“On the 24th, my friend called me at 5am from Kiev to tell me they were bombing them. I sat down and cried. I didn’t know what was going on,” she recalls.

Like many, she thought the attack would last a day, maybe two, “until they get what they want. But then I started thinking; what do they want? Why? It was chaos…when you wake up and your friends and family are getting shot at and shelled – Jesus, in the 21st century…"

She trails off. Words are coming out of her mouth, but she's still grappling with what they mean. Ordinary words strung together to explain the extraordinary.

Just yesterday, she tells me, a woman came in to volunteer.

"An average family - her son plays football, her husband works," she recalls.

But now, she's in a hotel, where she's responsible for her son and the other children on his football team.

“I asked what her husband does, where he is, how he’s doing. She told me he’s in the trenches," Tatyana recounts.

"I tried not to cry – she held her tears back as well – but it was hard.

“A lady this nice, this generous and upbeat. You wouldn’t think for a moment that, as we speak, her husband is in a trench somewhere.

"What if it was my husband? You don’t know that, when you wake up tomorrow, you’ll be able to speak to him – or is this the last word he says to you, tonight on the phone?

"I - Jesus Christ - I couldn't..." she trails off again. Lost for words, again.

On the first day, glued to her phone, she read and cried, listened and cried, worried and cried.

“I decided that I had to do something, or else I would lose my mind,” she says.

“I thought, crying for 24 hours and sitting at home – I would rather be useful.”

The page is full of names. Flip the page, more names. Flip again, even more. Flip, flip, flip – names and names penned in black and blue, small and big and neat and rushed, on cockled page after cockled page.

They’re the lucky ones who got out. It would be ludicrous to think in any other times – but these are the happier stories.

A mother lines up behind the desk and asks quietly for bread and milk and rice. Her little boy packs a canvas bag in silence. She adds her name and draws a little heart next to it. Another name.

Lexis was born out of Tatyana’s need to do something – anything – to help.

Initially, there was little aid formally organised, and she had difficulty finding ways to help. For a few weeks, she ferried families from Ukraine to Hungary with her own car, but she wanted something larger than just herself.

She managed over 200 people in her old job - she knew she could do it.

So she founded Lexis.

They help around 15 to 20 families per day now by giving them basic donations like food, clothing, toiletries, and toys and books for the children.

“We’re here the whole day. We work, we laugh, we talk – and then every night, I cry. And then the next morning, it’s easier to get up and work again. There’s no time for this during the day,” explains Tatyana.

The volunteers, who are all refugees, work and eat together, and slowly, they find themselves laughing again.

“We try to make a routine, not just talking about the war, but things like the kids’ schools, plans for the day,” she says.

“First, everyone wanted to help. Then, as suddenly as it all started, a lot of the support stopped. Now, there are days we get no donations,” she explains.

Employers and organisations that work with Ukrainian refugees receive funding, although this is allocated at the government’s discretion.

“I’m hoping we will get more support – although I might be naïve – because I know Europe gives money to Hungary to help the refugees, and the volunteers. But until now, we’ve not seen a cent of that,” Tatyana says.

“I was ashamed to say it at first, because I’m a volunteer, but I also have a family. We need the money to reach us. If it comes, then I want to continue to do this.”

Lexis currently receives one million HUF, which is around £2,200 GBP, from the UN per month.

“This is enough for…well, let’s take this Saturday, for example. We are holding an event, a 'mother and child' day, from 11am to 6pm.

“We will have an opening ceremony, anthem, prayer. We are expecting 120 people – that’s how many signed up in an hour and a half after we posted the event. We had to lock it after that because that’s how many we can host. If we had four million, for example, we wouldn’t have to limit attendance – everyone could come.

“We will have a bouncy castle, artists who will work with the children – 70 children and 50 mothers. We will have a cook-out –Hungarian food and vareniki, and sandwiches and water throughout the day, and little gift bags for the children after.

“The sports field is free, but we are also paying for psychologists and advisors to come speak to the mums. After two months, people are starting to wake up again to live their lives, and they need things like hairdressers and doctors. So, for one month, with four million HUF, we could do that.”

Vadim is working on getting information about the tax refund for charities, because Lexis is eligible for the rebate – but the Hungarian government has been criticised for making funding information inaccessible.

A little more would do a lot, says Tatyana.

“The mums want to get together on Sundays for tea, for example. We would like to have a bigger building with more rooms, so we can invite psychologists with the mums in one room, while the children can play in the other room,” she says.

Currently, they are in the basement of a building, with access to a kitchen and a storage room.

“Our volunteers and the refugees we know – they want to be with us, they need the community. We want a space where we can do this,” Tatyana says.

She looks at her watch – she has to leave because she needs to set up the sports field for Saturday.

As Tatyana leaves, another woman lines up behind the desk. She asks quietly for bread, milk and rice. She signs her name into the notebook.

To support the Lexis Foundation for Ukrainian Refugees, you can donate in person in the UK at the following address:

24 High Street

Luton, Bedfordshire

LU49LF

You can support the Lexis Foundation financially by transferring to:

Budapest Bank

IBAN HU61 10104167 62527100 01001009

SWIFT BIC BUDAHUB

For information, you can see their Facebook page at: https://www.facebook.com/groups/lexisalapitvany/

To contact Lexis, call Tatyana at +36307449465.