A man set out to sea to raise the future leaders of a nation

David Cooke went to Zambia and Botswana to teach in 1969: what he didn’t know is that he would find love, a soulful companion, and that the students he taught would go on to become leading figures of society - Ahisha Ghafoor

David's slender frame stands 6 feet 3 inches high, “You’re lucky it’s not cricket season,” he says imitating a batsman as he does some qigong exercises in a Chorlton park, Manchester. The rain has started to fall but he’s picked a spot, under some trees. Over us, the few leaves that are still intact offer little cover. As droplets trickle down, he shares his story.

David born in Lewisham, July 1945, grew up in Middlesex, his father was a middle-class accounts manager, his mother from working class rural Yorkshire. They met in the navy during the war. “Mum was from the wrong side of the tracks,” he jokes. David now 75, travelled to Zambia in 1969, after completing his studies in social studies at Salford College of Advancement.

Like almost every other socially motivated teacher, he felt it was his civic duty and wanted to be on the right side of the tracks. “I went because I was 23 and I wanted to do good in the world,” he says. Zambia had become independent a few years before. The World Bank had helped build some secondary schools but there weren’t any teachers because nobody had been trained.

He went there to do a postgraduate teaching course, as part of an alliance with several universities, the only condition was that he had to stay there for a number of years and teach. Thirsty for adventure, he was more than happy to go ahead with this. Merryn, his wife joined the same programme a year later.

The school library, Madiba 1975.

The school library, Madiba 1975.

The journey there

His first experience of life there were the halls of residents in Lusaka, which he shared with other ex-pats from Britain, Australia, and Canada. “You would mix a little with Zambian students but there weren’t a lot of them, it was a bit like being in a university, having a group of British pals.”

David travelled by boat. He could have flown, but he chose to travel by sea. He first arrived in Cape Town, South Africa and got on a Black-only bus with a priest he met on the boat. “I wanted to understand what was going on, how people were being oppressed.”

Later, he took a four-day train journey up to Lusaka: “I remember seeing the diamond mines, wild animals at times through the window, oh the landscape,” he exclaimed. “We crossed over the Victoria Falls by night eventually arriving at a town called Livingston. We all had to get off and I said look, tapping on my pockets I haven’t got any money. I had spent it all in Cape Town.” He asked if he could sleep on the train and they agreed.

“Very good were they, the Zambian people, they said if you behave you can sleep here. And the next day it was a slow train up to Lusaka. A Zambian policeman bought me a meal, he bought me rice and beef stew, spinach, I still remember,” he pauses, “welcome to Zambia, two very nice kind things.”

Eventually, he was sent to a rural secondary school in the western province, 400 miles away. The journey up was on a rocky second world war Douglas C47 Dakota plane. He stayed there for three years enjoying the delightful simplicities of life, a comfortable bungalow, the school which he could look out to from his kitchen window, and a local bar. There was time, but little to grow tired, “we were all pretty motivated really. There was a local bar, a bit of drinking, Merryn said I did too much drinking,” he laughed off.

When he left the UK, he knew he wouldn’t see or speak to his family for four years, they wrote to each other weekly and it was enough to keep him from getting homesick. “You go back now, and they all have ipads, and they’re all on their phones. They’re all interconnected, so it’s a transformation in that respect – I’m not sure if it’s a good thing.”

He recalls: “I would write home each week, and I eventually I got the Guardian weekly, so I subscribed to that, it helped. I remember feeling very motivated and to do well by the kids. The pupils were very motivated, you wouldn’t have a problem of order,” he smiles, “they were very keen to learn.”

Merryn reads her vows on their wedding day infront of friends in Kalabo, Zambia 1972.

Merryn reads her vows on their wedding day infront of friends in Kalabo, Zambia 1972.

A timeless romance

When we met to speak again, I asked him what his life have been like if he hadn’t have gone? “I wouldn’t have met Merryn, that’s a big thing, I would have been in big trouble without her.”

Merryn was posted to the same school in Zambia a year after he had arrived. “There were 13 bachelors, as she likes to say it, and I was the lucky one. We got together after about a year and married there a year after, which was very different.” Overhearing us Merryn, comes into the room and says, “48 years it’s been,” placing a tender hand on his shoulder. “There you are Merryn, here’s a good picture of you,” he says pointing to one of their trip to Botswana in 2015. Their bond, the old-fashioned kind: warmth, care and affection woven into stories that spread over a lifetime.

They married in July, 1972 Kalabo in Zambia. “We were without parents on both sides. Merryn's parents had come out to visit, but she had not met mine. They were from Croydon. My folks went over on our wedding day and raised a glass. I had a mum, dad, granny and a dog, Merryn had the same” he said before adding, “and a sister, we each had a sister.”

The girls show off the skirts Merryn taught them to make, Madiba, Botswana.

The girls show off the skirts Merryn taught them to make, Madiba, Botswana.

What are we contributing to?

The schools were open to all in Zambia, but still, as often is found in developing nations some families couldn’t afford to lose a pair of hands labouring in the fields. “We were in a very rural area,” he says, “it wasn’t a well-off part of the world.” They taught in Zambia from 1970 to 1972 in a school that had over 800 pupils on roll, there were 5-year groups. “All the girls were in the two bottom screens,” he pointed out, “the gender pressure was enormous.”

After three years, they started to realise that the education curriculum was very academically focused, as time went on it became clearer that western schools had become islands with no relevance to the country. They felt that they were contributing to a schism in society where students now looked down on the rural areas.

“We were very idealistic and heard that they had a different system in Botswana. We hitched hiked on our honeymoon from Zambia to Botswana, through Rhodesia with a low-level civil war going on,” he laughs, “and we went on to Madiba, to a school that wasn’t fully built yet. It had an academic side, but they also had brigades.” Something we would now refer to as vocational studies offering education in production, mechanics, plumbing and carpentry.

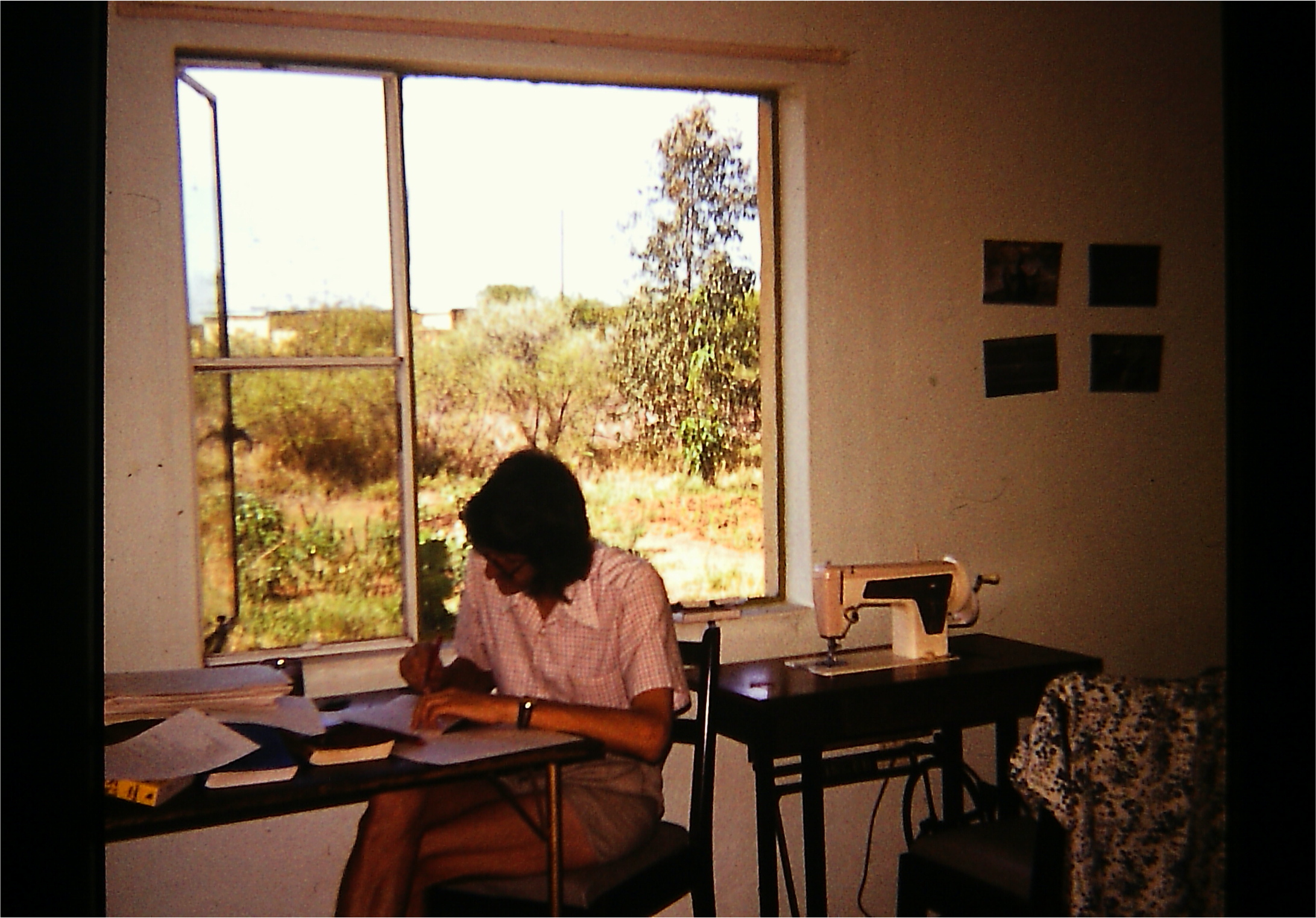

Merryn with her students in Madiba, Botswana doing developmental work on nutrition, linking up with the local hospital – the posters read ‘breast feeding is best’

Merryn with her students in Madiba, Botswana doing developmental work on nutrition, linking up with the local hospital – the posters read ‘breast feeding is best’

In Botswana, the role of women was different too: “they were very much equal. Botswana was tied into apartheid South Africa; the men would go work in the mines and the women were left at home to lead the households. Girls grew up seeing women assertive at home and that was reflected in schools, girls were just as academic.”

“All the students also had to do work in the community links, – help build a clinic or something.” The opportunity to train young people in life skills that contributed to society and the refreshing gender equality fit in with their idealistic values, they decided to stay there for five years. David taught maths and development studies or as he referred to it, “political consciousness,” whilst Merryn taught geography and domestic sciences.

David embraces Zola Zembe (second right) as he is reuinted with his family in Botswana, 1979.

David embraces Zola Zembe (second right) as he is reuinted with his family in Botswana, 1979.

The covert operation

In Manchester, 1973, David met Zola Zembe, a young South African trade union organiser who once shared a cell with Nelson Mandela. He was working for the South African Congress of Trade Union, to raise awareness and press for sanctions. In fear of his safety, he made the decision to flee South Africa, tearing a gaping hole between him, his home and his roots.

His family was left in Ciskei near King Williams Town. When Zembe caught wind that David and Merryn were going to Botswana to teach, he asked if they would venture to Ciskei to see his family and send back news.

Never shy of adventure, that’s what they did during the Christmas break of 1975, Zembe’s kids by then were all teenagers or older.

Zembe working as a "garden boy' during his stay with David and Merryn

Zembe working as a "garden boy' during his stay with David and Merryn

As part of his activism, Zembe would occasionally travel to Botswana, incognito of course, as the South African security forces would have taken the first opportunity to capture him. He sometimes stayed with David and Merryn, acting as their garden boy. “That was fun,” said David, “having a senior person in the African National Congress clean up my garden.” In 1979, it was arranged for his family to travel up with his brother from Ciskei so that he could see his children – almost 15 years to the day he last saw them - an emotional and overdue reunion.

The schools sports day in Madiba, Botswana.

The schools sports day in Madiba, Botswana.

The impact of an age

They revisited Zambia later from Botswana, in about 1977 and by then almost all the teachers were Zambian. In Botswana, 35 years later, their old colleagues and friends Archie and Elvidge had retired, “come back,” they said, “we have time - let's show you around.”

What they saw going back was different from the ‘bush’ they had come to call home. Now, water pipelines and electricity ran across the country. “And the development is wide-spread,” he signified.

Geo-politically, Botswana has always been relatively stable with a successful succession of tribal ruling of chiefs that consulted its people before passing laws, and then as a democratic nation with free elections and press. Its history is to merit: As the threat of occupation steadily started pounding the vulnerable walls of the country, three chiefs of Botswana travelled to England to meet with the Secretary of State Joseph Chamberlain.

In 1897, they put forward their case, Chamberlain went on holiday, came back, and then granted Botswana protectorate status. At the time, this was a favourable alternative to falling under apartheid South Africa, if they did their history would have been quite different.

As big as France, Botswana is about 200,000 square miles, with not much more than two million people. In the late 1970’s they discovered diamonds. Elvidge, his old friend and colleague, helped to ensure that the country got a fair deal. “What Elvidge ensured happened, is that local people got trained in the diamond industry, so they knew what they were looking for, what they’re talking about and how to recognise them and knew all the processes from cutting and polishing and so on." It managed to resist the exploitation of the diamond industry, such as that in Liberia and Sierra Leone.

David's development studies students pose to camera, Madiba, Botswana.

David's development studies students pose to camera, Madiba, Botswana.

There are half a dozen different ethnic groups in the country, a bilingual community speaking Setswana and English. Under the leadership of their first elected President, Sereste Khana, the state heads agreed that if the country was to find oil, gold, or any natural resources it would be nationally owned, it wouldn’t belong to the people but the country. They agreed to this before independence.

Later, when diamonds were discovered the wealth of the diamonds went on developing the country, improving healthcare and infastructure. Clinics and primary schools were built in villages with electricity – It’s the development that David and Merryn had hoped for: “they’ve done a lot to share the wealth of the country and some of the people I worked with were a part of that,” he said proudly.

The students they saw as grown adults 35 years later had leading positions in the press, politics, transport, human and womens rights, education and human resources – helping shape the country that stands today.

“At the time we knew we were getting people through their exams, what we didn’t know was the brilliant work some of the students had gone on to do. So that was really gratifying,” said David. “To see how well the county had done, and individually, so many of them have done very very well.” Merryn often reminds him that one of her best students, Letse Boho said: “Sir you have open-eyed me.” “And that was the development studies thing, developing his consciousness,” he said.

Elvidge Mhlauli with David, on the main road from Gabarone north, 2015. Elvidge was a teacher colleague at Madiba school. He became a headteacher, and later a Permanent Secretary of Botswana.

Elvidge Mhlauli with David, on the main road from Gabarone north, 2015. Elvidge was a teacher colleague at Madiba school. He became a headteacher, and later a Permanent Secretary of Botswana.

What would their future have been like if he hadn’t have gone and taught in Botswana? “If there hadn’t been that system, the opportunities were one of two: you would either work locally on subsistence farming or what you might have done is migrated to South Africa, apartheid South Africa.” Which for most was a long way to go. The reality is that if Botswana hadn’t modernised it would have taken much longer to integrate into the world economic system.

“I came to appreciate aspects of African society and culture very much. When we came back from Zambia, we were very anti-consumerism, why do you need ten varieties of garden peas to choose from. There was something about the strength of community and interdependence of people. And some of the political people we met were inspiring, against injustice,” he said.

David and Merryn reuniting with an old student in Madiba, Botswana 2015.

David and Merryn reuniting with an old student in Madiba, Botswana 2015.

Upon their return to the UK, they decided to settle in Manchester. Merryn had been to Liverpool university and David, Salford. It was a question between Liverpool and Manchester. “Manchester had a film theatre at the time, and we had been watching John Wayne westerns at the school for three years, and we wanted to see some good films, so we chose Manchester,” he says with his chirpy laugh. They bought a house in the September of 1980, in Chorlton and have been there ever since.

David left Botswana in 1979, a term early and before the students had taken their final exams. Before he left, he took a black and white photograph of them. When he got back to Manchester, he made sure to print off 30 copies, individually write their names on them and send them back. He wanted them to have this, a copy of the picture.

35 years later, February 2015, David and Merryn were standing outside the Ministry of Education and Odiretse – an old student - came out and said, “Oh Mr Cooke, Mrs Cooke, the dress you helped us make and Mr Cooke look…” out of her bag she rummaged a little and took out a photograph. “For 35 years she’d been carrying that photograph,” he said, throat heavy and taking a moment to reflect, “she said, ‘education was so important to us, we really valued what you did for us.'”

David and Merryn stand outside their home in Chorlton, Manchester, 2021.

David and Merryn stand outside their home in Chorlton, Manchester, 2021.