'People think you're not a normal woman if you don't

want kids'

A decline in UK birth rates has sparked a rise in 'pronatalism' to increase the population. But how does that make the childless feel?

Fiona Powley has always known she didn’t want to have children.

The 49-year-old was told repeatedly throughout her 20s and 30s that she would feel differently when she was older, or if she met the right man.

But she didn’t.

So she chose not to have children - even though that choice has been met with criticism.

“There's an assumption that you're not a normal woman if you don't have this biological urge,” said the life coach.

Despite these reactions, Fiona is not alone. Many women feel the pressure to have children. And this pressure has only increased with the rise of pronatalism - the pro-population growth movement that encourages the bearing of children.

Since 2012, the fertility rate in the UK has been declining year-on-year. Fertility rates measure the number of children born per woman of childbearing age. In 2023, the latest data, there was the lowest number of births since 1977.

Brought into the mainstream by Elon Musk and JD Vance, fears about the impact of declining birth rates have allowed pronatalist beliefs to take root in the UK.

At a National Conservatism conference held by a US-based think tank in 2023, former Conservative MP Miriam Cates said the low birthrate was “the one overarching threat to British conservatism, and to the whole of western society”.

And demographer Paul Morland went even further, arguing for a “negative child benefit” tax for those who do not have offspring as “it recognises that we all rely on there being a next generation and that everyone should contribute to the cost of creating that generation”.

While such drastic measures are unlikely to be introduced, they do beg the question of where childless people belong in a pro-natal culture.

“There's a sort of idea that we're socially expected to do it, and there's also an idea that somehow it's inbuilt in every woman that you should want to procreate,” Fiona added.

UK-based charity Population Matters campaigns against pronatalism.

In 2021, it published the Gilead Report to “protect women’s rights from pronatal politicians”, arguing that “panic over population decline is driving abuses such as restrictions on contraception access, abortion bans and hostile propaganda targeting childfree people”.

Much of the discussion about why birth rates are declining centres around the cost of living. But is this really the reason?

Not for everyone.

Fiona Powley runs the Bristol Childfree Women group, which now has around 1,000 members. The group is largely made up of women who are childfree by choice.

And when she asked members of the group if they were childfree for financial reasons, most women said it wasn’t the primary reason for their decision. Instead, they saw being more financially stable as a benefit of being childfree, rather than a motivation.

Fiona said: “The number one word that comes up time and time again in the responses is freedom, absolute autonomy.

“If people are sitting there thinking women are choosing not to have children because they're putting their careers first, that's not what's happening.

“These people are criticised, but they're actually being very responsible. We criticise people for having babies when they don't have the income or the support to support them properly.

“But then, if they choose to not have them or delay, we criticise them because they should be birthing children.”

The responses of the women from Bristol Childfree Women seem to suggest that having children seems unappealing to some British women because they feel it will restrict their personal freedom.

"If people are sitting there thinking women are choosing not to have children because they're putting their careers first, that's not what's happening."

This is not the case for all developed nations.

France has the highest fertility rate in the EU. Many demographers suggest this is some part due to policies which make it easier to have children, such as reducing tax bills for families and subsidising creches for under threes.

In the UK, childcare is much less accessible.

In 2023, one in five parents with children aged four and under reported problems with finding childcare flexible enough to meet their needs. And more than a third of parents found it difficult or very difficult to meet their childcare costs, which is the highest proportion since 2014.

Just before her 40th birthday, Stephanie Joy Phillips was told she could not be a mother due to infertility. Though she wanted children, she still feels judged for her lack of them, saying that childless people are often looked at with pity, negativity, and ignorance.

“Through grief you've got all these dark, dirty, horrible emotions that are natural but you need to release them and it's again extremely hard to do that when your grief is disenfranchised,” she said.

Stephanie began a Facebook group for childless women after she discovered she was not represented by infertility support groups, who gave details about other ways of becoming a parent but did not offer any support about coming to terms with being childless.

After one week, she had 100 submissions of blog posts from childless women. Seven years on, the group has nearly 2,000 members from across the world.

She then founded World Childless Week, both to give visibility to the growing number of childless people and help these people to find community and feel less alone.

“You initially think you’re the only childless person because you can't see anybody else. You see mums everywhere and families but not the childless,” says Stephanie.

“Those of us who are childless not by choice often get told, couldn't you have tried harder? Was there not more you could have done? Don’t give up, I'm sure you could adopt or look at surrogacy and it's a push to try and fix you, to get you into the 'mumgang'.

“We live in a pronatalist world so anybody who doesn't become a parent is automatically looked at with a strange sense of who are they? What's going on? Why don't they have children?

“It needs to be a conversation with children at a very young age so they grow to know they may be a parent, they may choose not to be a parent or they may not be a parent but not by choice and that all those options are valid.”

"We live in a pronatalist world so anybody who doesn't become a parent is automatically looked at with a strange sense of who are they? What's going on? Why don't they have children?"

And it is not just childless women that feel out of place in a pronatal society. Many men do, too.

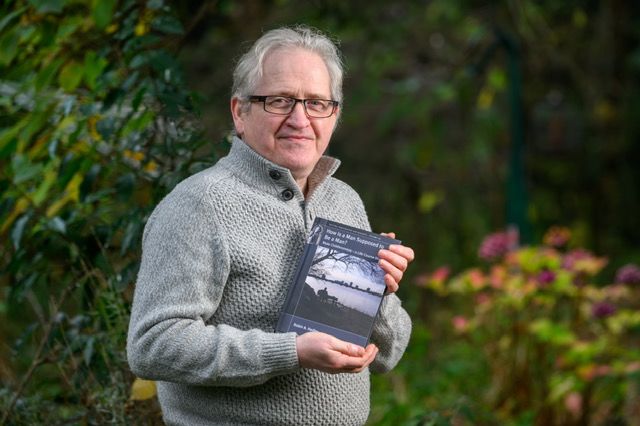

Robin Hadley, a leading expert on the psychological and sociological impact of male childlessness, wanted to have a child but was unable to do so.

After getting married and divorced in his 20s, he struggled to pay his mortgage and so couldn’t afford to go out much, making it difficult to meet someone.

For Robin, involuntary childlessness was not a result of physical infertility but social infertility - when people are unable to have children due to social or relational circumstances.

“It's a lot more complex than just infertility, but infertility dominates the media and the narrative and that's because lots of people make lots of money from it,” he said.

Childless men are vacant not only from conversations but from national reproduction statistics, with the ONS collecting no data on male fertility.

Dr Robin Hadley by Paul Cooper

Dr Robin Hadley by Paul Cooper

“It's a lot more complex than just infertility, but infertility dominates the media and the narrative and that's because lots of people make lots of money from it.”

Dr Robin Hadley by Paul Cooper

Dr Robin Hadley by Paul Cooper

A British Cohort study found that levels of childlessness are higher among men than women in the UK, with 25.4% of men childless compared to 19% of women.

Hadley believes that the assumption that men are indifferent to having children is a myth fuelled by society’s denial of male vulnerability. His research challenges the view that men are not as affected by involuntary childlessness as women.

His research found that men are only marginally less broody than women. Compared with 71% of women, 69% of men had experienced yearning for a child.

For his book ‘How Is a Man Supposed to Be a Man? Male Childlessness – A Life Course Disrupted’ Hadley interviewed 14 men aged between 49 and 82 who wanted to have children but haven’t for his 2021 book.

Another issue Hadley’s research explores is the child gap, with older childless people typically entering formal care at an earlier stage in illness and remaining in care longer than people with children. Currently 92% of unpaid care is provided by the family.

Older people who don’t have children to help look after them are 25% more likely to need to go into a nursing home, according to the campaign group Ageing Without Children.

Hadley added: “All the men I've interviewed have said unprompted, there's something missing. There's obviously a child missing, but there's something missing inside. There's something missing in the experience, and there's something missing in the social status you have because you're not fulfilling the pronatalist ideal.

“It's quite easy for me to say now that I really wanted to be a dad, but I didn't become one because my social status isn't hinged on it, but in your 30s, for men and women, it sort of is.”

Pronatalism may be growing, but the projected birth rates are set to grow, too.

The Office for National Statistics predicts the fertility rate will have risen to 1.59 children per woman by 2045, compared with 1.56 in 2023.

Whether that unfolds remains to be seen.

But in the meantime, both childfree and childless people like Fiona, Stephanie, and Robin ask for a little understanding.