Idealism v Realism: Researcher Dr Joel Rookwood on whether Germany’s idealistic approach to football is viable in England?

The constant rumblings and debates surrounding Brexit for the past few years have raised deep questions about whether England, as a sole nation, is outward or inward looking.

One where we ask if we are capable of looking past ‘a small-minded island outlook’ and to other countries as examples.

When it comes to football, Germany’s idealistic approach remains the best counter point for what England gets wrong in its expression of identity through football, but whether it’s a viable solution remains a difficult question to answer.

Global football researcher and lecturer at UCLAN University, Dr Joel Rookwood, has worked across six different continents with interests in fan culture, mega events and management.

His breadth of experience both at home and abroad lends itself to perspective from all angles of the English game – one in which he understands the English psyche in the wider context.

“The English love their football, but they don’t know it very well and that’s the reality,” he told me.

“We have a confidence about our history and we think we understand it.

“I’ve been to 170 countries and I’ve watched football in most of them and, the more I travel, the more I realise I don’t really know much about it at all.

“I think that’s a healthy position to start from and perhaps more English fans should be more open minded about what football is and what it can be.

The rise of sporting directors

Becoming outward looking is a process that can come from the very top and putting a finger on why ‘globalised’ Premier League clubs are not always willing and receptive to change is puzzling.

German clubs in particular have shown how their club models can effectively create a whole club ethos- one in which there is a transparency across all levels from the board to the fans.

Some smart thinking people in English clubs have recognised that progressing towards a more continental sporting director model is one that pushes football clubs to become more strategic and cohesive.

Rookwood explained to me that the rise in clubs switching to the sporting director model is ultimately about providing sustainability- one where there is a clear vison in the medium to long term that identifies both a way of playing and way of recruiting and a first step in being outward in approach.

He said: “We are just finding out about sporting directors in this country and it’s still very much a case that we are discovering.

“I think, talking about cohesion, the fans on a wider scale here don’t really get it and I think a lot of clubs are just as equally unsure about it because it’s really new and it’s a very diverse demographic of people that are taking up these roles.

“I don’t think it’s a perfect system, but most people will now look at a club that doesn’t have one and say they need one because cohesion is paramount. “

It could be argued that the Premier League has established an environment where there is an inherent distrust both within and between English clubs – one in which fans are treated as customers and consumers and remain distant from those in charge.

Consequentially, it’s not surprising that some fan bases are receptive to further hierarchal change.

As Rookwood explained to me from his experience, English fans will not concern themselves with the board as much as they perhaps should, regardless if it’s the chairman or the sporting director.

“Liverpool’s Bill Shankly famously spoke about the holy trinity of a football club between the manager, the fans and the players and he said the board are just there to sign the checks,” he commented.

“The sporting director is threatening that traditional way of thinking so the fans are sometimes not that conscious about it.

“A lot of time, fans will reduce it to recruitment policies, and if the star signings are good players then they think the sporting director is great. That’s where the conversation ends as there isn’t any connection there.”

Despite this, Liverpool’s steady rise under what could be loosely be described as the German model is perhaps the most successful example at the very elite level of the English game.

Jürgen Klopp’s arrival in 2015, swiftly followed by the arrival of the internally appointed sporting director Michael Edwards a year later, transformed the fortunes of the club both on and off the pitch.

Like clubs in Germany, Liverpool recognised the benefit of looking among their ranks and Klopp and Edwards have since formed a formidable team at Melwood.

In an article for Joe at the time of Edwards appointment, journalist and club insider Tony Barrett explained that Edwards and Klopp already shared a strong working relationship in the club.

In his words it brought together a cohesion across all levels, one in which there was “a consistency in approach and a sense of collective endeavour.”

As Rookwood explained: “Under Klopp, things changed and they are now heralded as the best run club in the world and Liverpool have been that for the last two and half years.

“For me that’s less of an opinion, but an objective reality.

“None of this would happen without Klopp, he is integral.

“But what the sporting director does is it allows good people to do their job -it allows a division of pressure.

“Klopp is brilliant at saying I can’t do everything. I’m going to get the best people around me.

“I go through the club now and everyone there has a clear idea of their role. The closer you look at the intricacies of that the rosier it looks, it’s a long term solution to a problem.”

Could there be a universal implication of the German model in England?

Liverpool aren’t the only English club using the German model as a blueprint.

The on field success of former Premier League outfit Norwich City has been accredited in due part to their sporting director Stuart Webber.

At Norwich City, as in his previous position at Huddersfield Town before, Webber identified the need for a cultural change which would help further the clubs identity to one that truly resonated with their fans.

In appointing Borussia Dortmund’s then under 23 coach Daniel Farke, a coach familiar with the German model, he was able to create a level of transparency across the club – one that eventually aided the club both on the pitch as well as off it.

By all accounts the Canaries fan base and their community remained open minded about the approach and willingness to buy into his vision.

Webber was aware that simply trying to take something from one culture and expecting to work in your own is useless unless you are willing to apply the cultural relevance to your city and your community.

But as Rookwood rightly pointed out, this unique outlook means it’s a hard model to implement universally.

“It’s a totally different context as they (Germany) have been using this model for years,” he said.

“It’s like asking why the German fans stand, well they were never told they have to sit.

“It’s kind of always been an element of their culture to have sporting directors in the way European clubs are sports clubs with football as one of their branches.

“These are all culturally engrained, they haven’t just decided to make those alterations and changes.

“So ultimately, there isn’t one picture for what works. I think football fans are still in the dark about what a sporting director really does. “

Rookwood suggested that, from the outside looking in, Norwich understand that and have taken the opportunity to educate their fans about the sporting director role and to have this level of transparency. But for bigger teams such as Liverpool, perhaps this is unrealistic.

“For bigger clubs, I think the circle of trust has to be tiny and tight nit and a lot of that is to do with transfers,” he said.

“If you look at the pursuit of Fabinho from Monaco after the conclusion of the 2018 Champions League final there was interest from both United and Liverpool.

“If Liverpool’s interest was leaked then United would possibly make a move before them.

“Everything about Liverpool’s model is efficiency of process because we are not known for being a wealthy club, despite being a big club.”

The differing outlook of German football fans and English football fans

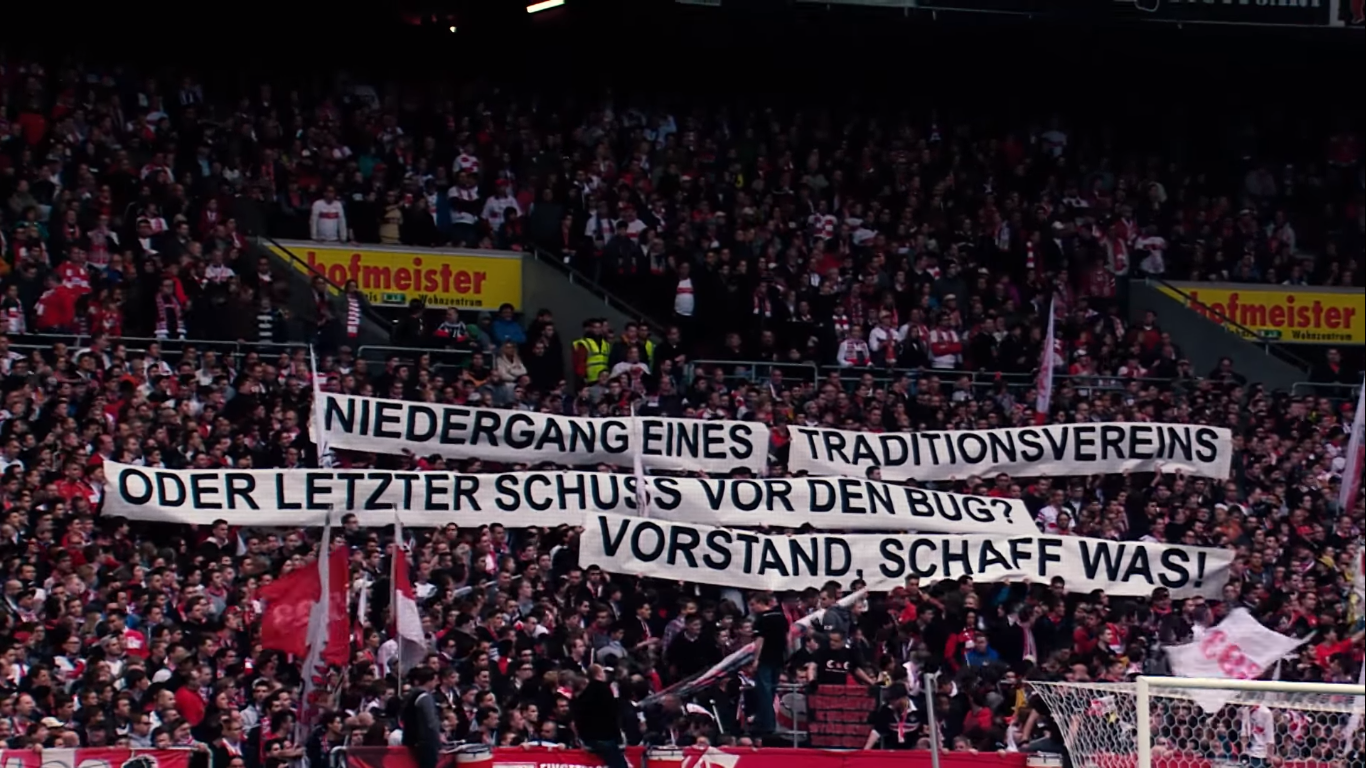

In drawing comparisons, Rookwood explained to me that what Germans fans have and the English don’t is solidarity and commonality in voice.

In late February, Eintracht Frankfurt protested against Monday night football in a Bundesliga match against 1.FC Union Berlin.

They left their stadium part empty and replaced it with one banner that displayed a simple message ‘no to Mondays.’

Despite the announcement that it would be taken out as part of the next TV deal, protests have continued across the board throughout Germany on the matter with fans voicing their displeasure.

Rookwood, as a Liverpool season ticket holder himself, has tried to open up the conversation among fan groups around football in a wider context in England in the same way they do in Germany.

However, from experience he tells me that English football remains too oppositional and antagonist for anything constructive to be done.

“They (the German fans) will go to a stadium on mass, stand outside as both sets of fans and chant football needs to be affordable. So they’ll do that,” said Rookwood.

“When was the last time English fans got together to do anything?

“One of the problems is the fact we have one of the biggest national network of football clubs.

“We ultimately have too many fans and too much in fighting between them. You’d never get United and Liverpool fans in the same room.

“I know because we tried to do it through the Football Supporters Federation about 12 years ago and I was in the room representing Liverpool.

“We just ended up having bitchy little arguments about who had won the most league titles, we didn’t get anything constructive done at all.

“There is too many oppositional factors which is why fans are ultimately taken for a ride in this country.”

The state of identity in English football

Rookwood’s points touches on an engrained problem that has been sustained by the Premier League for over three decades which, as he describes, is quite deliberately manufactured by those with commercial interest that wanted to shift the demographic of English football away from traditional football fandom.

In the wake of Hillsborough, and the problems of football in the early 90s, there increasingly became moves away from fandom in order to marginalise terrace culture and eradicate hooliganism.

All of which sowed the seeds for the lack of a ‘footballing DNA’ that England is now desperately trying to fix.

Rookwood suggested that what makes up a component of an identity in many respects is simply down to two principals – ‘what you are and what you are not.’

Ultimately clubs, as he describes, are custodial entities of cultures that they don’t maintain themselves. Cultures and identities must be organic from the bottom up and that starts with the fans and what they stand for.

“I am heartened by clubs like Crystal Palace for whom, when they come to Liverpool, sing about Palace and about their area of London and they are setting the tone,” he said.

“That group have been moved behind the goal now and that speaks of the centralisation of that movement to that football club - smaller clubs could do that.

“When I take about the essence of identity I talked about who you are and who you are not and too many clubs in this country are obsessed with who they are not instead of celebrating who they are.

“I think that is the biggest thing English fans need to get over.

“We all seem to go through the rituals of singing about our rivals when we go abroad and it’s weird and it’s boring.

“Instead of that we need to enjoy it a bit more and take a leaf out of the Germans book by singing about who we are, what we do and what we stand for.

“Once you start doing all those things, there is more potential of conversation through fan groups when it’s not built on antagonism.”

Although context suggests that implementing the German model universally may be difficult, Rookwood make’s an interesting point of mentality of the fans and how they can affect the identity of their football clubs.

What German football clubs seem to do better than any other is recognising that they cannot win all the time and that “success comes in many forms” as journalist Jonathan Harding put in his book Mensch: Beyond The Cones.

They exemplify that going to a football match can be about a sense of connection to the people around them and there is an enjoyment of the process and not an obsession with the outcome.

Rookwood suggests that it’s this idealism from Germany that English football can realistically bring into the game.

“I think generally in life happiness comes when you appreciate the journey that you’re on rather than constantly looking ahead,” he said.

“We need elements that look back and elements that look forward, but we generally find happiness fundamentally when we live in the present.

“I think football fans that recognise that are football clubs that build communities to allow for that long term planning.

“The big part of it is spoken about that at that level, but if you look at fans that’s what they want to do. They want to enjoy it. ”